|

|

|

||||||

Review from The Illustrated London News, January 9th, 1892

None

of the signs of a triumphant success were wanting to

distinguish the production of Messrs. W. S. Gilbert

and Alfred Cellier's new comic opera, "The Mountebanks" at the Lyric Theatre. This event, thrice postponed in consequence of the illness and death of the composer, ultimately took place on Monday, Jan. 4, in the presence of a crowded and brilliant audience. Mr. Gilbert is never so amusing or so incomparable as when he is dealing with paradox and looking serious over the most delicious absurdities. It is not difficult to trace in the story of "The Mountebanks" the leading motive of "Creatures of Impulse" grafted to a slight extent upon that of "The Palace of Truth", and worked out with plenty of variation, variety, and, let us add, freshness of detail.

None

of the signs of a triumphant success were wanting to

distinguish the production of Messrs. W. S. Gilbert

and Alfred Cellier's new comic opera, "The Mountebanks" at the Lyric Theatre. This event, thrice postponed in consequence of the illness and death of the composer, ultimately took place on Monday, Jan. 4, in the presence of a crowded and brilliant audience. Mr. Gilbert is never so amusing or so incomparable as when he is dealing with paradox and looking serious over the most delicious absurdities. It is not difficult to trace in the story of "The Mountebanks" the leading motive of "Creatures of Impulse" grafted to a slight extent upon that of "The Palace of Truth", and worked out with plenty of variation, variety, and, let us add, freshness of detail.

The first act is an admirable piece of construction. We are at a lovely spot somewhere in Sicily, not far from a Dominican monastery, with Etna burning peaceably in the distance. The dwellers in this picturesque neighbourhood are all more or less in a state of commotion. A secret society, calling themselves the "Tamorras", are just commencing a series of weddings, that will convert all their members into married men. The landlord of the local inn is much exercised by the conduct of an old alchemist who resides on his second floor, and who insists on gradually blowing himself to pieces in his dynamite experiments. Suddenly there arrives a party of mountebanks, unfortunately minus their leading attraction — two clockwork figures, got up to represent Hamlet and Ophelia. However, the proprietor, Pietro, is a man of resource, and he sees a way out of the difficulty provided that his clown, Bartolo, and his dancing girl, Nita, will impersonate the automatic hero and heroine of Shakespeare's tragedy, which, in due course, they consent to do. Such is the aspect of affairs when suddenly the old alchemist dies, leaving behind him nothing but a small bottle containing a potion that has the extraordinary gift of changing all who drink of it into precisely what they pretend to be. This wondrous phial falls into the hands of Pietro, who forthwith empties its contents into his wineskin, and administer doses to his two subordinates in order to lend greater vraisemblance to their delineations.

The first act is an admirable piece of construction. We are at a lovely spot somewhere in Sicily, not far from a Dominican monastery, with Etna burning peaceably in the distance. The dwellers in this picturesque neighbourhood are all more or less in a state of commotion. A secret society, calling themselves the "Tamorras", are just commencing a series of weddings, that will convert all their members into married men. The landlord of the local inn is much exercised by the conduct of an old alchemist who resides on his second floor, and who insists on gradually blowing himself to pieces in his dynamite experiments. Suddenly there arrives a party of mountebanks, unfortunately minus their leading attraction — two clockwork figures, got up to represent Hamlet and Ophelia. However, the proprietor, Pietro, is a man of resource, and he sees a way out of the difficulty provided that his clown, Bartolo, and his dancing girl, Nita, will impersonate the automatic hero and heroine of Shakespeare's tragedy, which, in due course, they consent to do. Such is the aspect of affairs when suddenly the old alchemist dies, leaving behind him nothing but a small bottle containing a potion that has the extraordinary gift of changing all who drink of it into precisely what they pretend to be. This wondrous phial falls into the hands of Pietro, who forthwith empties its contents into his wineskin, and administer doses to his two subordinates in order to lend greater vraisemblance to their delineations.

But he does not bargain for the whole of the assembled company drinking also and compelling him to swallow his  share. that, however, is what actually occurs, and as it happens that at this particular moment everybody is pretending to be what he or she in reality is not, the effect of the potion is only too complete. The second act, which takes place at the monastery by moonlight — a superb "set" — gradually unfolds the mischief that has been done. The Tamorras have been turned into monks; while their pretty little confederate, the newly married Minestra, has become the aged crone whose face and voice she simulated. Teresa, the village beauty, having made believe that she is mad, is now really out of her mind. Finally the sly Pietro is suffering tortures such as he himself depicted, and the hapless Bartolo and Nita have exchanged their humanity for Geneva clockwork. Needless to add that some diverting incidents arise out of these various metamorphoses. The situation is handled with undeniable skill, and the only fault is that it is somewhat too prolonged. This act, unlike the first, grows a trifle tedious, but the defect can easily be remedied by the omission of one or two vocal numbers, and arriving more rapidly at the application of the antidote which restores all the afflicted personages to their original condition.

share. that, however, is what actually occurs, and as it happens that at this particular moment everybody is pretending to be what he or she in reality is not, the effect of the potion is only too complete. The second act, which takes place at the monastery by moonlight — a superb "set" — gradually unfolds the mischief that has been done. The Tamorras have been turned into monks; while their pretty little confederate, the newly married Minestra, has become the aged crone whose face and voice she simulated. Teresa, the village beauty, having made believe that she is mad, is now really out of her mind. Finally the sly Pietro is suffering tortures such as he himself depicted, and the hapless Bartolo and Nita have exchanged their humanity for Geneva clockwork. Needless to add that some diverting incidents arise out of these various metamorphoses. The situation is handled with undeniable skill, and the only fault is that it is somewhat too prolonged. This act, unlike the first, grows a trifle tedious, but the defect can easily be remedied by the omission of one or two vocal numbers, and arriving more rapidly at the application of the antidote which restores all the afflicted personages to their original condition.

To this whimsical story, Mr. Alfred Cellier has wedded some delightful music. The libretto of "The Mountebanks" was the first that Mr. Gilbert had entrusted to anyone but Sir Arthur Sullivan. He may not have found in Cellier a musical humorist of equal calibre, but for sweetness and grace of melody and general charm of light opera style, the composer of "Dorothy" could hold his own with most Englishmen. Among the lyrics of the new opera are some of Mr. Gilbert's happiest efforts, and their spirit is reflected, for the most part, with skilful and sympathetic art. Take, for example, Teresa's first song:—

How admirably the tripping rhythm suggests the pert manner here assumed by the Sicilian coquette! Then take as a contrast the wiling ballad sung by the same damsel in the second act, after she has become crazy : —

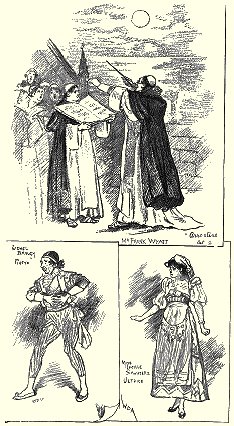

The chief of the Tamorras, in the person of Mr. Frank Wyatt, has a splendid song: —

while the refrain with its crescendo shout in the "Hi, hi, hi!" is simply irresistible. But perhaps the most popular tune of all will be that sung by the irritable automata: —

To show that there is humour in Mr. Cellier's muse we have only to point to his treatment of the "chants" sung by the monks (real and otherwise) and the facility wherewith he combines their solemn declaration: —

| Earthly pleasures that allure, |

| For an hour we abjure — |

with the joyful waltz-air sung by the girls: —

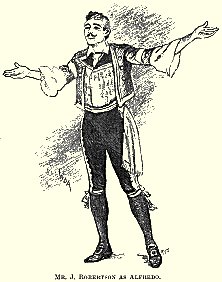

Enough having been said to prove that the score of "The Mountebanks" is full of bonnes bouches, we shall  devote our remaining words to the performance. First and foremost stand Mr. Harry Monkhouse and Miss Aida Jenoure (a débutante which London must henceforward make its own), the clever and humorous pair who embody Bartolo and Nita. Of all Mr. Gilbert's odd creations, these are surely the oddest and it would be impossible to imagine them more perfectly realised. The "eccentric" methods of Mr. Wyatt and Mr. Lionel Brough are effectively displayed in the parts of Arrostino and Pietro, while other comic characters are well filled by Messrs. Furneaux Cook, Arthur Playfair, Charles Gilbert and Cecil Burt. On the other hand, the higher vocal honours of the representation rest with Miss Geraldine Ulmar (a charming Teresa), Miss Lucile Sanders (Ultrice), Miss Eva Moor (very piquant and pleasing as Minestra), and Mr. J. Robertson (a good-looking and interesting Alfredo). The mis en scène is superb in every detail, Mr. Percy Anderson's dresses being in design and colour exquisite. The grouping and stage-management are worthy of Mr. Gilbert's practised art, while the training of the entire company reflects the highest credit upon Mr. Caryll, whose entr'acte (founded on one of Teresa's ballads) had to be repeated on the first night. The reception of the opera was altogether enthusiastic.

devote our remaining words to the performance. First and foremost stand Mr. Harry Monkhouse and Miss Aida Jenoure (a débutante which London must henceforward make its own), the clever and humorous pair who embody Bartolo and Nita. Of all Mr. Gilbert's odd creations, these are surely the oddest and it would be impossible to imagine them more perfectly realised. The "eccentric" methods of Mr. Wyatt and Mr. Lionel Brough are effectively displayed in the parts of Arrostino and Pietro, while other comic characters are well filled by Messrs. Furneaux Cook, Arthur Playfair, Charles Gilbert and Cecil Burt. On the other hand, the higher vocal honours of the representation rest with Miss Geraldine Ulmar (a charming Teresa), Miss Lucile Sanders (Ultrice), Miss Eva Moor (very piquant and pleasing as Minestra), and Mr. J. Robertson (a good-looking and interesting Alfredo). The mis en scène is superb in every detail, Mr. Percy Anderson's dresses being in design and colour exquisite. The grouping and stage-management are worthy of Mr. Gilbert's practised art, while the training of the entire company reflects the highest credit upon Mr. Caryll, whose entr'acte (founded on one of Teresa's ballads) had to be repeated on the first night. The reception of the opera was altogether enthusiastic.

Page modified 30 August, 2011