|

|

||||||

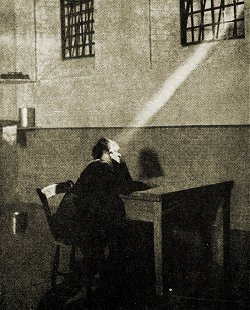

The Hooligan was Gilbert's last play: it was first performed at the Coliseum Music Hall on 27th February 1911, just over three months before his death. This little play set in the cell of a condemned man is also one of his most interesting. It is certainly among his best "serious" works.

Music halls were, of course, not the usual setting for serious drama. The Lord Chamberlain only permitted plays of thirty minutes or less, and with six speaking characters or less, to be performed in music halls. For the most part the halls shied away from serious drama, but Oswald Stoll, manager of the Coliseum, was made of more ambitious stuff, and wanted to win commissions from the major dramatists of the day. Gilbert was the first to take up his offer; afterwards, Shaw allowed Stoll to perform How He Lied to Her Husband and J.M. Barrie The Twelve Pound Look, but Gilbert's The Hooligan remained the only major original work to come out of Stoll's plans.

The title role of the hooligan, Nat Solly, was played by James Welch, a music-hall favourite apparently more known for his comedy than for pathos. (Interestingly, however, he played the comic role of Lickcheese in the original production of Shaw's first play, Widowers' Houses, in 1892.) He seems to have been highly effective in this dark melodramatic role, and the play as a whole was something of a "shocker": Mrs. Alec Tweedie noted that "It was so gruesome that women had gone out fainting, and it turned my blood cold." An unexpected parting shot from the respectable old dramatist, Justice of the Peace for Middlesex, knighted in 1907 and living the life of a country gentleman at Harrow Weald: but then, Gilbert had always made a point of not doing the expected thing.

There is very little plot: the play is, as the subtitle tells us, "a character study". Nat Solly, a young East End hooligan, has been condemned to death for murdering his girlfriend. We see him as he wakes up on the morning of his execution, hysterical, self-pitying, self-justifying. Yet for all his ugly whining, there is sympathy for him too: we are made to see how intolerable his predicament is. He pleads for leniency on account of his weak heart, and because he didn't mean to kill her, only to "cut" her to teach her a lesson. A step is heard outside the door. He thinks they are here to take him to execution, but it is the Governor arriving to tell him that his sentence has been commuted to penal servitude for life. Nat Solly, unable to bear the shock of this news, dies of a heart attack.

The play is not easy to read: Gilbert's attempts to transcribe Cockney speech often get in the reader's way. But once this barrier has been penetrated we see that Gilbert has succeeded in painting the portrait of a real man — not pleasant but human, not clever but believable. Aside from the clever double-whammy of the ending, there is no plot mechanism to get in the way of delineation of character, and as in his earlier character piece Sweethearts (1874), the result shows him to be surprisingly good at such pure character-writing. It is good to know that Gilbert went out on such a high.

Notes by Andrew Crowther

- Microsoft Word Format [24Kb]

- Text Format [20Kb]

The play script was submitted to the G&S Archive by Andrew Crowther.

Page modified 31 July 2011