HISTORICAL NOTE

On 10 February 1869, Dr. Philip H. Williams, the Honorary Secretary for the Three Choirs Festival which was to be held in Worcester that year, wrote to Sullivan saying that the Executive Committee had heard with great pleasure that he might be willing to write "a work" for the Festival the following September. The work was to be an oratorio – a musical setting of a religious text for solo singers, chorus and orchestra in dramatic form – and the subject Sullivan chose was The Prodigal Son.

Sullivan selected his own text from the scriptures, and composed the music astonishingly quickly in a little over three weeks. He asked Rachel Scott Russell, a young lady with whom he was having a "romantic liaison" at that time and who was constantly urging him to concentrate his energies into serious music, to copy the music. She replied:

The Prodigal is too beautiful and it made me weep to read it. I rejoice to do the copying, and I want you to conduct from my copy – will you, I should so like it, and I will try to do it beautifully and make as few mistakes as possible.1

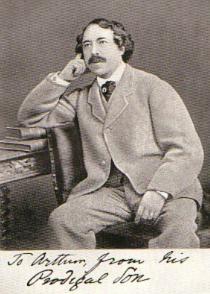

|

| Sims Reeves |

The Prodigal Son received its first performance in Worcester Cathedral on 10 September 1869 with great success. Sullivan conducted, the soloists being Therese Titiens, Zelia Trebelli, Sims Reeves and Charles Santley. Rachel Scott Russell was there and the following day wrote to Sullivan:

I am far prouder of The Prodigal than of anything. The divinity of your gift of God breathes through the whole work and it is a glory to have written a thing which will stir men's souls to their depths, as it does, and make them feel better and nobler, even if it is transient. You know now what your gift is – and you will use it. That hour in the Cathedral yesterday was perfect happiness and everyone is talking even here of your success.2

After the Worcester premiere, a further performance was scheduled for 18 December 1869 in London at the Crystal Palace. Sims Reeves found himself double booked for that occasion, and the performance was brought forward a week. However, Sims Reeves still failed to appear, absenting himself on his frequently applied plea of illness. Two days after that performance, in a letter to the critic Charles Gruneisen, Sullivan wrote:

...and finally I am thrown back upon Perren! The choruses went well, Santley as usual was magnificent, giving me the idea that he was working all the harder to make up for my disappointment...[But] as far as the Prodigal's part, thank God not a note was heard except the accompaniment – it left no impression at all upon the audience. In fact it was Hamlet with the part of Hamlet omitted. I must say the public were very good natured and ... enthusiastic to me personally ... In Memoriam went superbly.3

Reeves was not the only original soloist who was absent on that occasion: a Mlle. Vanzini substituted for Titiens.

Sullivan's old teacher, Sir John Goss attended the Crystal Palace performance and wrote a long letter containing many complimentary remarks to Sullivan on 22 December 1869. However, he closed with a note of caution:

You are an admirable conductor. The band seemed to me most capital in your hands, the Chorus seemed to do very well...All you have done is most masterly – Your orchestration superb, & your effects many of them original & first rate...Some day you will I hope try another oratorio, putting out all your strength, but not the strength of a few weeks or months, whatever your immediate friends may say ... only don't do anything so pretentious as an oratorio or even a Symphony without all your power, which seldom comes in one fit.4

The following year there was a performance of The Prodigal Son in Manchester conducted by Hallé, it was repeated at the Three Choirs Festival at Hereford in September, and in November it was performed in Edinburgh with Sullivan conducting. During his visit to America to supervise the "official" New York production of H.M.S. Pinafore and launch The Pirates of Penzance, Sullivan found time to conduct a performance by the Handel and Haydn Society in Boston on 23 November 1879.

However, it seems that despite its initial success, the work did not establish a regular place on the concert platform. Writing in 1899, B. W. Findon states:

That the work is now only heard at long intervals is no disparagement to its worth as a composition, for although the oratorio-loving public will courteously listen to novelties, perhaps give a grateful ear to them a second time, their standard is the Messiah and Elijah, and unless an oratorio has the captivating power of Handel, or the mellifluous quality of Mendelssohn, it has no chance of being even temporarily enrolled among the people's favourites.5

Of the music of The Prodigal Son, Percy Young wrote:

The Prodigal Son, as Goss suggests, betrays a lack of commitment. In this work Sullivan, like many other composers, was unable to escape from the limitations placed upon him by a God-fearing public which misread respectability for piety. But there are a number of places where the music comes to life, often stimulated by fine details of orchestration. In bar 5 the side-drum enters, followed at a distance of three bars by timpani and wood-wind. Five bars later the double-bassoon is introduced. In the tenor aria 'How many hired servants' (No. 11) there is beautiful colouring by solo oboe, muted strings and delicately shaded flutes, while in 'There is joy' (No. 2) – which was written in D but marked 'a note lower' in the autograph – a background of clarinets, bassoons, four horns and organ effectively gives way to organ only. In 'My son attend to my words' (No. 4) the exhortation to 'trust in the Lord' swings into a broad, confident tune in 3/4 time, cheerfully anticipating the virile measure of Parry. In 'Let us eat and drink' (No. 6) a tiny 'oriental' figure, such as Sullivan frequently used in his operas, flickers across the score. In 'They went astray (No. 15) there is some splendidly dramatic writing in gaunt canon – first for soprano and bass, and then for alto and tenor – against an empty orchestral background. Here Sullivan is at his most economical and his most effective, and way ahead of his British contemporaries.6

Like all British composers of his generation, Sullivan not unreasonably believed that if music for great occasions was to be written it was best done by paying due regard to Handel. The last fugal chorus of The Prodigal Son is Handelian in outline, but is, alas, too restricted in movement to carry conviction.7

He later concludes:

As a composer of oratorio, Sullivan was obviously not uninfluenced by Handel and Mendelssohn, but certainly in The Prodigal Son ... he attempted definitions of character and of scene that removed their subjects some way from the pulpit interpretations of the period.8

Paul Howarth

Notes:

- Undated letter

- Letter dated 11 September 1869

- Letter dated 13 December 1869

- Letter dated 22 December 1869

- B. W. Findon:Sullivan as a Composer in Arthur Lawrence: Sir Arthur Sullivan,1899

- Percy M. Young: Sir Arthur Sullivan, 1971

- ibid.

- ibid.

- To Prodigal Son Home Page.

- To Sir Arthur Sullivan's Other Music Page

- To Opera Index

- To Gilbert and Sullivan Archive Home Page.

Page updated 16 September 2003