|

|

||||||

AN ILLUSTRATED INTERVIEW WITH

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN

BY ARTHUR H LAWRENCE

Part 1

"Polly! What's the time?" obtrusively cackled the elderly parrot whose cage hangs in one of the rooms of Sir Arthur's delightful retreat at Walton-on-Thames. It was a wonderfully fine afternoon, and this was my final call on Sir Arthur Sullivan in regard to this article. Sir Arthur had just finished writing the opening bars of his rendering of the Christmas hymn, "It came upon the midnight clear," so that it might form a souvenir-autograph for this issue of THE STRAND MAGAZINE.

The experience throughout — from the time that I had my first chat on the subject in the study of his town house in Victoria Street — had been such a pleasant one that, as Polly, apparently happy in its exceedingly limited powers of human expression, reiterated her chuckling inquiry for the third or fourth time, the query served to remind me that even journalistic inquisitiveness has its finality, no matter how delightful the process may have proved — to the interviewer.

Sir Arthur's loquacious parrot is, I am afraid, only a vague humorist, and whether or no the bird's insistence upon knowing the hour of the clock may have acted as a valuable hint to innumerable callers — though this is mere speculation on my part — yet the reiteration of the word "time" might well be made the basis of a more serious text, for each succeeding year has served to give an added lustre to the fame of our greatest English composer; and, moreover, although Sir Arthur is now in his fifty-sixth year, his energy has not one whit abated. In talking with him, it is indeed difficult to realize that his first composition — the music to Shakespeare's "Tempest " — was composed so far back as 1860, and that his first opera was produced thirty years ago. Indeed, Sir Arthur Sullivan's professional experience extends over a very considerable period of our wonderful Victorian Era, and furnishes by no means the least important part of its history. Rarely has any man's work achieved such success in a lifetime, and as during that period Sir Arthur has known everyone worth knowing, it may fairly be said that his reminiscences, if ever he cared to write them, would form one of the most interesting volumes of autobiography ever published. To the fertility of his rare genius Sir Arthur Sullivan has added an infinite capacity for unceasing hard work. There is hardly any phase of musical composition which he has not treated and beautified, and the fruit of his wonderful versatility is to be found in oratorio, hymns, songs, and cantatas, as well as in the ever-popular Gilbert-Sullivan operas, which have been such a source of "innocent merriment," and a perpetual delight, to hundreds of thousands on both sides of the Atlantic. One of the happiest features of what is, perhaps, the most distinguished artistic career of our own time is the real personal popularity which has kept pace with the spontaneous and far-reaching recognition which has been accorded to Sir Arthur Sullivan's genius as a composer. Although without prejudice on the subject, Sir Arthur is not particularly amenable to the wiles of the interviewer, so that from this point of view I may perhaps add my own humble testimony to the fact that, although I have worried Sir Arthur on many occasions, I have always been struck with his unfailing and wholly natural courtesy — "old-fashioned" some people might term it; but, if so, one must be pardoned for hoping that it is an old fashion which will never get quite out of date.

Sir Arthur was the younger son of Mr. Thomas Sullivan, a clever Irishman who from 1845 to 1856 occupied the position of bandmaster at the Military College, Sandhurst, whilst his mother was descended from an old Italian family, and the Italian blood in his veins may, perhaps, serve as an explanation — to those who are curious in questions of heredity — for the almost un-English vivacity of manner which is one of Sir Arthur's most salient characteristics, whilst he has added to it a very English (or Irish) dogged determination and persistence, a quality which has been remarkably displayed in the way in which he has done his best work under the greatest difficulties, and a great part of his most melodious and most humorous light operas were composed and orchestrated in the midst of illness and in the intervals of great physical pain.

"Yes, that was the first time I saw my name in print," and Sir Arthur points to a cutting from the Illustrated London News, dated 1856, which is framed and hung on the wall, announcing the fact that Master Arthur Seymour Sullivan, aged fourteen, had won the Mendelssohn Scholarship; and it is easy to see from the composer's manner that no subsequent "notice", of whatever character, has ever given him equal pleasure. Then comes a tour of exploration round the house in search of personal photographs and similar curios reproduced in these pages, and to which it will be possible to refer later on.

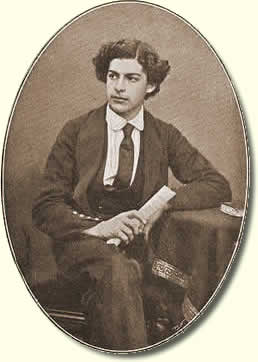

Young Arthur Sullivan's practical training in orchestral matters began very early, for there were hardly any instruments in his father's band at Sandhurst which he did not learn to play with facility. Mr. Sullivan was happy in the belief that his younger son possessed rare musical ability, although he could have had no conception of the pre-eminent distinction which his son was destined to attain. At the age of eleven nothing would satisfy the embryo musician but that his father should get him into the choir at the Chapel Royal. "His voice was very sweet," said Mr. Helmore, who was then master at the Chapel Royal, "and his style of singing was far more sympathetic than that of most boys." The young musician was only three years in the choir, yet long enough to make his first attempt at musical composition. He was the author of a boyish effort, "0 Israel," and an anthem, which was duly sung in the choir. Sir Arthur referred to these very early efforts with a smile of compunction, but it was in part due to this training that — when, in 1856, the Mendelssohn Scholarship was instituted — the erstwhile chorister came out at the head of the list. It may be of interest to mention that Sir Joseph Barnby was one of the candidates. "And so it happened," said Sir Arthur, "that I did not experience any exceptional struggles or difficulties when I began my profession, for the winning of the scholarship gave me a certain prestige and many good friends, so that I took some very pleasant letters of introduction with me when I left England to study in Leipzig. Yes, that portrait of me (when a student at Leipzig) was taken when I was eighteen, and when I was in the throes of my first serious composition, the 'Tempest' music, which was not produced in England until two years afterwards, when I was twenty."

The success which attended the "Tempest" music, when it was produced at a Crystal Palace Concert on the composer's return to London in 1862, was immediate and emphatic, and amongst those who came to hear it performed on the second occasion was the great novelist, Charles Dickens. He was waiting outside the artists' room as Sullivan came out, and going up to him and shaking him by the hand, he said: "I don't profess to know anything about music, but I do know that I have listened to a very beautiful work." Soon after this, Dickens accompanied Chorley and the then Mr. Sullivan to Paris, and Sir Arthur told me:–

"I always found Dickens a most delightful companion. Apart from his high spirits and engaging manner, one might give two special reasons for this," said Sir Arthur. "On the one hand he was so unassuming — he never obtruded his own work upon you. I have never yielded to anyone in my admiration of Dickens's work; but, speaking of him as a companion, I can safely say that one would never have known that Dickens was an author from his conversation — I mean, that he never discussed himself with you ; whilst, on the other hand, I have often since wondered at the wonderful interest he would apparently take in the conversation of us younger men. He would treat our feeblest banalities as if they were the choicest witticisms, or the ripe meditations of a matured judgement"; and, as Sir Arthur smiled at the recollection, he told me how vividly he remembered the fine face, the keen eyes, and the varied expressions of the novelist's face, and how wonderfully it used to light up as he talked with you.

"There was quite a little coterie of us in those days," Sir Arthur continued. "First of all there were Charles Dickens and his daughters, Charles Collins, his son-in-law, and his brother, Wilkie Collins, and then there was Mrs. Lehmann, one of the married daughters of old Robert Chambers. Dear old Chorley used to have a house in Eaton Place, where we were wont to assemble and have little dinners. Browning was one of us. I liked him immensely, but as a conversationalist he was, at that time, somewhat overwhelming — you couldn't get a word in. It was marvellous how Browning sustained his interest in everything, especially in music. Up to the last he used to regularly attend the Monday Popular Recitals, and so on."

Perhaps, at this point, I may interrupt the narrative thread which must run through this article, to record Sir Arthur Sullivan's replies to my many questions as to his method of work. It is not only a point of particular interest, but it is one, I should imagine, about which many diversified theories are held. It is possible that the explanation which Sir Arthur gave me will upset a good many preconceptions as to "how it is done."

I think I had prefaced my queries by relating an anecdote I had read of a composer who, seized with an inspiration whilst out for a walk, had jotted down the opening bars of the melody on his shirtcuffs, and having no further material on which to record the great work, was struck with a happy idea, and, seizing a piece of chalk, had finished off the composition on the back of a passing plough-boy (by permission), the said boy heading the procession homewards, well in sight of the composer, who feared to lose sight of the most important part of his inspired composition.

Sir Arthur was immensely amused by the idea, which seemed to appeal to him as having been done by way of ingenious advertisement.

"No, I am afraid I have never had time to wait for inspiration," Sir Arthur exclaimed. "If one waited for the right mood, or for things to occur to one, one would, I should imagine, do little or nothing at all. I cannot say that anything ever 'occurs' to me until I have the paper actually in front of me. I don't use the piano in composition — that would limit me terribly."

In reference to the notion that the musician and the poet are seized by an inspiration, and then promptly begin work before the mood has passed away, Sir Arthur likened such an idea to a miner seated at the top of a shaft, waiting for "the coal to come bubbling up to the surface." "He has to dig for it," Sir Arthur exclaimed, and assured me that the very melodies in his work which appear most spontaneous were the result of particularly hard work and of constant re-casting.

"I can admit this much in regard to the inspirational theory," said Sir Arthur, "that in actual work a phrase does sometimes come into one's head which one feels bound to put in, and it will happen, of course, that one day work comes easily, whilst another day it is more difficult."

Then, taking the subject a step further, Sir Arthur laid particular stress upon one point of considerable interest, as it is a distinguishing feature of his method of work.

"The first thing I have to decide upon," said Sir Arthur, "is the rhythm, and I decide on that before I come to the question of melody. The notes must come afterwards. Take, for instance, the song from the 'Mikado':–

| The sun whose rays are all ablaze | |

| With ever-living glory. | |

You will see that as far as rhythm is concerned, and quite apart from the unlimited possibilities of melody there are a good many different ways of treating those words," and that I might not be unconvinced, Sir Arthur good-naturedly hummed the well-known lines several times, giving a different rhythm and different melody each time, so that I might perceive that the rhythm which was ultimately selected was best suited to the sentiment and construction of those particular lines.

"You see, five out of the six methods were commonplace, and my first aim always is to get as much originality as possible out of the rhythm, and then I approach the question of melody afterwards. Of course, Sir Arthur continued, "the melody may always come before metre with other composers, but it is not so with me. If I feel that I cannot get the accents right in any other way, I mark out the metre in dots and dashes, and not until I have quite settled on the rhythm do I proceed to actual notation.

"The original jottings," Sir Arthur added, showing me one or two packages containing the "sketches," i.e., the original composition, for some of his operas, "are quite rough, and would probably mean very little to anyone else, though they mean so much to me. After I have finished the opera in this way, the creative part of my work is completed but then comes the orchestration, which, of course, is a very essential part of the whole matter, and entails very severe manual labour. The manual labour of writing music is certainly exceedingly great. Apart from getting into the swing of composition itself, it is often an hour before I get my hand steady and shape the notes properly and quickly. This is no new development," said Sir Arthur, smilingly. "It has always been so, but then, when I do begin, I work very rapidly. But, whilst speaking of the severe manual labour which is entailed in the writing of music, you must remember that a piece of music which will only take two minutes in actual performance — quick time —- may necessitate four or five days' hard work in the mere manual labour of orchestration, apart from the original composition. The literary man can avoid manual labour in a number of ways, but you cannot dictate musical notation to a secretary. Every note must be written in your own hand — there is no other way of getting it done; and so you see every opera means four or five hundred folio pages of music, every crotchet and quaver of which has to be written out by the composer. Then, of course, your ideas are pages and pages ahead of your poor, hard-working fingers!"

To continue the description of the method of work as regards the operas, Sir Arthur went on to explain:–

"When the 'sketch' is completed, which means writing, re-writing, and alterations of every kind, the work is drawn out in so-called 'skeleton score' — that is, with all the vocal parts and rests for symphonies, etc., complete, but without a note of accompaniment or instrumental work of any kind; although I have all that in my mind," Sir Arthur continued.

"Then the voice parts are written out by the copyist, and the rehearsals begin; the composer, or, in his absence, the accompanist of the theatre, vamping an accompaniment. It is not until the music has been thoroughly learnt, and the rehearsals on the stage — with action, business, and so on — are well advanced, that I begin the work of orchestration.

"When that is finished the band parts are copied, two or three rehearsals of the orchestra are held, then orchestra and voices, without any stage business or action; and, finally, three or four full rehearsals of the complete work on the stage are enough to prepare the work for presentation to the public."

Meanwhile the full score has been taken, and from it an accompaniment to the voice parts has been "reduced" for the piano — this work has recently been undertaken by Sir Arthur's secretary, Mr. Wilfrid Bendall, himself the composer of numerous successful operettas and cantatas; so that the "words and music" — that is to say, the music for the piano and the voice part — is ready for the public by the time the piece is produced. After a full-dress rehearsal, to which the favoured few are admitted, comes the "first night," when, as on so many happy occasions, we have had the privilege of seeing Sir Arthur "conduct" the performance in person. Here the composer's work ends, and this is, I think, a faithful record of the whole process, from the time that the libretto is handed to the composer, and Sir Arthur studies the rhythm and works out "the sketch," until the eventful night when the rap on the desk of Sir Arthur's baton is the signal for the overture which precedes the rise of the curtain.

"The science of musical notation," said Sir Arthur, meditatively, "is really a most wonderful thing. There is no single phrase or combination of phrases, not a sound or combination of sounds, that you cannot express on paper, and which cannot be reproduced from that piece of paper a hundred years hence."

Reverting to the labour which musical composition entails, Sir Arthur discussed for a moment or two the "rough-and-ready" method in which music of a kind can be made. The composer conceives some sort of melody, then someone else writes it down, a third person fits in the accompaniments, while somebody else scores it for a band. "Yes, it's an easy way," said Sir Arthur, good-humouredly, "but the result is not quite a work of art!"

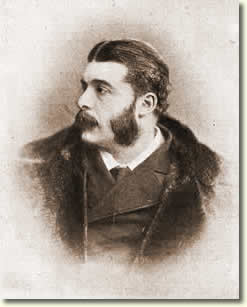

Sir Arthur Sullivan's meeting with Mr. Gilbert over twenty years ago has been well described in a previous issue of THE STRAND MAGAZINE, but it must be remembered that long before that occasion Sir Arthur had become versed in the ways of the stage and the writing of operatic music. The performance of opera in Paris, when he visited the city with Chorley and Dickens, made a great impression upon him, and with characteristic energy he determined to learn something of the technique of the stage. This wish was granted by his being given the position of organist in the Covent Garden Opera in the old days when the late Sir Augustus Harris was a schoolboy, and his father, a sketch of whom accompanies this article, was to be heard ejaculating, " Eh! what?" and flourished exceedingly.

Young Mr. Sullivan's musical facility was soon discovered and was much in request. The work he was called upon to do was not wanting in variety, and the way in which his genius was made to serve what one feels at the present time to be almost base ends is decidedly amusing.

"On one occasion," Sir Arthur said, "I was admiring the 'borders' that had been painted for a woodland scene. 'Yes,' said the painter, 'they are very delicate, and if you could support them by something suggestive in the orchestra, we could get a pretty effect.' I at once put into the score some delicate arpeggio work for the flutes and clarionets, and Beverley (the artist) was quite happy. The next day probably some such scene as this would occur. Mr. Sloman (the stage machinist) : 'That iron doesn't run as easily in the slot as I should like, Mr. Sullivan. We must have a little more music to carry her (Salvioni) across. I should like something for the 'cellos. Could you do it?'

"'Certainly, Mr. Sloman, you have opened a new path of beauty in orchestration,' I replied, gravely, and I at once added sixteen bars for the 'cello alone. No sooner was this done than a variation (solo dance) was required, at the last moment, for the second danseuse, who had just arrived. 'What on earth am I to do?' I said to the stage-manager; 'I haven't seen her dance yet, and know nothing of her style.' I'll see,' he replied, and took the young lady aside. In less than five minutes he returned. 'I've arranged it all,' he said. 'This is exactly what she wants' — giving it to me rhythmically — 'Tiddle-iddle-um, tiddle-iddle-um, rum-tirum-tirum, sixteen bars of that ; then rum-tum rum-tum, heavy, you know, sixteen bars and then finish up with the overture to "William Tell" last movement, sixteen bars, and coda.'" With a celerity which he has equalled on many occasions at a much later date, the composer wrote the necessary quantity of "that," and it was in process of rehearsal in less than a quarter of an hour.

But the rapidity with which Sir Arthur Sullivan works is indeed surprising when one recollects the power, originality, and beauty of the result. His first opera, "Contrabandista," was composed, scored, and rehearsed within sixteen days from the time he received the libretto. The overture to "Iolanthe" was commenced at 9 p.m. and finished at 7 a.m. the next morning. That to "The Yeomen of the Guard "— the opera which is now running merrily as a revival at the Savoy — was composed and scored in twelve hours; whilst the epilogue to the "Golden Legend," which for dignity, breadth, and power — as a well-known critic once stated — stands out from amongst any of his choral examples, was composed and scored within twenty-four hours. Apart from the creative part of the work, such manual dexterity is indeed almost incredible.

Sir Arthur told me that, although "The Mikado" and "Pinafore" would probably receive the popular vote, "The Yeomen of the Guard" was his own favourite work in light opera, because the story told is of more sustained and dramatic interest, and afforded him better opportunity for more sentimental and serious work.

Amusing stories are related of the rage which "Pinafore" created everywhere, although curiously enough it went very slowly at first. The rage extended to America, and in a newspaper of the time there is a notice to the effect that in one city alone a hundred thousand barrel-organs were built to play nothing but "Pinafore"! "What, never? Well, hardly ever!" became a catch phrase of the most fearful type. One distracted editor found himself compelled to forbid the use of the phrase by his staff on pain of instant dismissal. "It has occurred twenty times in as many articles in yesterday's edition," he sorrowfully said to them on one occasion. "Never let me see it used again!" "What, never?" was the wholly unanimous question. "Well, hardly ever," replied the wretched man.

This popularity, however, has not been confined to this country and America, for most of the operas have been translated and performed all over the world. I have been told amusing stories - which would not be germane to this interview - of the difficulties which the different translators have found in rendering some of the Gilbertian phrases into their own language, but happily music needs no translation and the quips and cranks, the catchy melodies, the amazingly clever orchestral effects with which lovers of Sullivan music are familiar, are a source of delight in all nations where music is understood and appreciated.

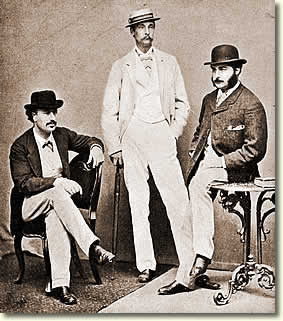

With regard to the illustrations which accompany this article, many of them portraits from one of his albums, there are two — both of them "groups" — which may need some little explanation. In one of them — "The Canterbury Pilgrims" — there are three figures. On the left is the late Fred Clay, the well-known composer; the centre figure is that of the Honourable Seymour Egerton, then known as Sim Egerton, now Lord Wilton, described by Sir Arthur as the ablest amateur musician in England. He is very happily attired in flannels, straw hat, and is fortified by the possession of a useful-looking umbrella whilst on the right is Mr. Arthur Sullivan, looking, perhaps, the most cheerfully negligent of the trio.

"We were portion of the wandering minstrels," Sir Arthur exclaimed, with an amused smile, as he gazed on the photo. "They were all amateurs, and I had no business there, but I was called upon to make up what was wanting, and my duty was to play the harmonium."

The other group is not less interesting, and is even yet more amusing. The distinguished people who sat for the picture gave a performance of Haydn's "Toy Symphony," at St James's Hall, 1880, under the presidency of Lady Folkestone, on behalf of a charity. It will be observed that Sir John Stainer played the triangle, Signor Randegger the drum (for which he was wholly unsuited), Messrs. Santley and Blumenthal the violin and rattle respectively, whilst Sir Arthur, in the foreground, holds an instrument with which, at stated intervals, he simulated the note of the cuckoo. Among other well-known faces are those of Sir Julius Benedict, Frederic H. Cowen, Wilhelm Ganz, Sir Joseph Barnby, August Manns, and Carl Rosa.

It should be added that the fact that the worthy conductor, Mr. Leslie, took the matter very seriously added much to the zest which the performers threw into their duties. However great may have been the humour of the thing, the affair was, aided by the presence of the Princess of Wales, a tremendous success, and there is no doubt that the whole musical world, which was so well represented in the executants, as well as the charity, felt a good deal happier for the performance.

Sir Arthur remarked that he found that work first and physical exercise afterwards was the natural order of things, and that it was impossible to reverse the process. "I find my best recreation in rest," he remarked, "and when I can spare the time I like to come down here, walk about the garden and read, varying this with a certain amount of brisker exercise, boating and so on, and occasionally indulging in a game of billiards, whist, or bzique.

"I can always read and re-read Thackeray's works," Sir Arthur told me, "whilst there are certain books of Dickens which I have read over and over again. I never get tired of his humour, but I do get tired of his sentiment. 'Pickwick' always seems fresh to me and this is true of 'Pendennis', 'Vanity Fair,' and 'The Newcomes.'" Sir Arthur told me that whilst he appreciated "Ouida's" word-pictures he detested the artificiality of her style. "Bret Harte I love," Sir Arthur added, "and when I travelled in California I realized the marvellous truth of his pictures both in regard to scenery and character." Speaking of other contemporary writers, Sir Arthur told me that he liked "healthy novels." Pressed for a definition, he instanced the work of Conan Doyle, Stanley Weyman, and Anthony Hope.

When speaking of the progress which Great Britain has made as a musical nation — she is now certainly the most appreciative musical nation in the world ; and although Sir Arthur would be the last man to allude to it, it is a progress which has been contemporaneous with his own career — "Yes," he remarked, "Great Britain is easily first in many ways — in the possession, for instance, of the greatest singers, and the best chorus singing. Nowhere can you get such a public for oratorios, whilst all-round executant ability has reached a very high standard ; but during the last twenty years music has been treated with a respect which it did not receive in my earlier days. When I first came back from Germany, there was hardly anyone who could sing a good song, and if you did find such a one, he or she was not listened to. The attempt to sing a song in a drawing-room was the signal for general conversation. This state of things has now passed away. Everywhere you find people who know how to play and how to sing, and what is more important, people who know how to listen."

Sir Arthur has already started on a new opera, the libretto of which will be by Messrs. Comyns Carr and Arthur Pinero. No date, of course, has been fixed, and it would be quite premature to say anything more, but Sir Arthur has already received the first installment of the libretto.

Lawrence, Arthur H. “Illustrated Interviews LVI – Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan.” Strand Magazine 14.84 (Dec. 1897) 649-658.

Page modified 24 November 2011