|

|

||||||

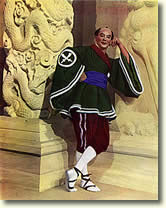

Filming The Mikado

[Green, Martyn. Here's a How-de-do, Max Reinhardt, London. 1952]

That summer also brought us to the filming of The Mikado. Discussions had been going on for some time between the interested film-makers and D'Oyly Carte. A Company was formed under the name of 'G. and S. Films, Ltd.', with Geoffrey Toye as the Producer and Director of Music. He had already been associated with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company as Musical Director during the 1919 and 1921 seasons at the Princes Theatre. The original intention had been to film The Yeomen of the Guard, and a shooting script had been prepared. When it was decided instead to film The Mikado my first reaction was one of disappointment. I am still of the opinion that it would have made a better picture than The Mikado, and in my view the script proved my point. Of course it may be that I had a sneaking preference for Jack Point over Ko-Ko, but I only say 'may be.'

We had fun making the picture, but it involved a lot of hard work. Victor Schertzinger was engaged to direct, and, as everyone knows, Kenny Baker played Nanki-Poo. John Barclay was in the title role, with Jean Colin as Yum-Yum and Constance Willis as Katisha. The D'Oyly Carte Chorus was engaged in toto, but the only active Principal members of the Company to be engaged were Sydney Granville, who proved himself a very fine artiste on the screen as well as on the stage, Elizabeth Paynter and Kathleen Naylor as Pitti Sing and Peep Bo, and myself. Gregory Stroud, who played Pish Tush, had done the Juvenile Baritone roles with the Company during the 1926 season at the Princes Theatre, and had only recently concluded a long contract in Australia with the Tait and Williamson G. and S. Company there.

All the music was recorded first and later 'shot' to a playback. This proved quite tricky at certain points. In 'Tit Willow,' at the line, 'He slapped at his chest' I had to emphasize the words with the appropriate action, and on the chosen recording the noise of the slapping of my open hand on my chest came in between the words 'slapped' and 'at.' Before the scene was shot I sat in front of a loudspeaker while they played the record at me with myself singing it at the same time. Facing me were Victor Schertzinger and the two chief cutters, Gene Milford and Philip Charlot, all watching my mouth to see that I was with the record the whole time, and all watching my hand slapping my chest to make sure that it synchronized with the sound on the recording. I wouldn't care to say how many times I went through it before they were satisfied, nor how many 'takes' were necessary before all were agreed that well perfect synchronization had been achieved as well as all the other aspects of a 'good take.' We were all day on the job, and when I eventually retired to my room to take off my wig and make-up I felt more like something the dog had left on the mat than a human being.

Recordings began while we had still a month to run at the Scala. They were all done at Pinewood Studios, beginning each morning at ten o'clock, and ending between five-thirty and six in the evening. That meant that I was on my way there by half-past eight, on my way back to the theatre by six, and beginning another two and a half to three hours' work by eight. There was little time for leisure. But that was not the worst of it. Recording over, shooting started. I decided, on the advice of Victor, to move out to Pinewood and live in the Club attached to the studios right away instead of waiting for the Scala season to finish. I was aided in this decision by the fact that I was due in the make-up room between four-thirty and five-thirty in the morning, and I couldn't see myself getting up around two o'clock every morning to get there. So, on my day off, my wife and I packed and moved out. For the next two weeks my time schedule was as follows:–

Rise at four. Make-up room at five. Make-up completed at seven. Between seven and nine, breakfast, snatch a few minutes of sleep, and get to the set. From nine till six I would be on the set, with a break for lunch of one or two hours. At six I would remove make-up, snatch a light meal, drive into town, make-up and play a show, remove make-up, dress, and start driving back at about eleven. Pinewood by midnight, a hasty small meal and a drink, and so to bed for a good four hours' sleep!

I kept that up, with the exception of matinée days, for a fortnight, and the Monday after we closed at the Scala I made my way into the make-up room at the usual time. Ernie Westmore was there waiting. I sat down in the chair, and he adjusted my skull piece, and got on with the groundwork of the make-up. When that was completed he began on my eyes.

'Look at the ceiling,' says he.

My activities of the last fortnight had reduced me to the absolute verge of exhaustion, and, as I rolled up my eyes, I fell out of the chair in a dead faint. When I recovered I was in my bed, and there I remained for the next three days, to the consternation of the whole of the executive staff. I was upsetting the whole of the shooting schedule. It incidentally taught me a lesson. It taught me that so long as I was willing to go in at four-thirty every morning, they would let me do it. I decided against. I bearded first Victor and then Geoffrey Toye in their respective lairs and suggested that a form of roster would be a good thing, thus ringing the changes on the 'early turn,' and that as I had been on it for the past two weeks they could put my name on the late one for the next two. I suggested that he of the past two weeks' late turn should now take pride of place. That meant Kenny Baker.

'But he's the 'star' of the picture !' I was told. 'That's impossible!'

I didn't waste time in arguing. I went to my doctor, and he told them in no uncertain terms that unless something better was arranged I should probably collapse completely. I'd had no rest for twelve months and would not be getting any for the next twelve. A roster was drawn up and agreed to, and from then on a good time was had by all.

Victor, whom I got to know very well, was about the most patient man on the set I've ever met. Ne25 August, 2011 or put out. He had a marvellous sense of humour, and was not beyond playing a practical joke. Granville was the butt of one of them, a joke which is, I should think, one of the oldest gags in creation. It was one of those days when nothing would go right for Granny, and for some reason he was muffing his lines. 'Take' after 'take' he would trip up over one line, until he became eventually something of a nervous wreck. Victor was the personification of Patience on a Monument, soothing him, encouraging him, urging him on. Practically the whole day had gone on this one scene. Then, at about a quarter to six in the evening, we started on another. It was a long scene, running five or six minutes and using a considerable amount of film, and Granny went through it perfectly. Victor was delighted end said so, and had just started to say that that would do for the day, that we would just go and see the 'rushes' of the previous day's shooting and then go home, when he stopped, and turning to the cameraman, Bill Skoll, exclaimed in a loud voice:–

'What! No — but, Bill, you should see that there is film in the camera before I give the order to shoot.' Then, turning to Granny, 'Did you hear that? He says he forgot to reload the camera. There was no film in it!'

There was deathly silence; then something like a wail came from Granny. I really thought he was going to burst into tears. But before he had been in his misery more than a few seconds Victor turned to Bill Skoll again with:

'Oh, you mean your own cine-camera! Well, if Mr. Granville would like to go through it again especially for you —' At this point he rose from his chair hurriedly and left the studio at a run, hotly pursued by Pooh Bah brandishing Ko-Ko's axe!

We were ten weeks all told on that picture, working right through what otherwise would have been my normal vacation.

Page modified 25 August 2011