Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

THE CONTROVERSY SURROUNDING

GILBERT'S LAST OPERA

by

AN EARLIER 'COLLABORATION'

Fallen Fairies was not German's first association with Gilbert as they had shared a brief collaboration some 31 years previously. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians - Volume 7; pg. 261, [Macmillan, London: 1980], lists under Works by Sir Edward German incidental music composed for a revival of Gilbert's blank-verse play Broken Hearts staged at the Crystal Palace in 1888. (It was first produced at the Royal Court Theatre in December of 1875.) However, this is very much overstating the case as German's contribution to the production was the setting of but one song.

With the aid of Julia Neilson, (a fellow student at the Royal Academy of Music who had then turned to acting with success), German was given an introduction to W. S. Gilbert, who had helped to foster her career. Her part in Broken Hearts called for a song in Act I for which, to judge from a later letter of German's, he had barely an evening to compose a setting. Known as Lady Hilda's Song it was scored pizzicato to give the effect of a mandolin accompaniment. Although Gilbert thought the music very charming and graceful, he subsequently decided that the play would be better without it. However German pleaded with the actress to use her influence to reinstate the song and in this she succeeded. Gilbert relented, writing: 'Since Mr German takes it so seriously, we will most certainly put back the song'. Lady Hilda's song, in which she seeks the extinguishing comfort of death, is decidedly melancholic in tone and German kept the vocal line within an easy compass. Unfortunately the composer's tribulations were not ended for Alfred Cellier, the conductor, thought the pizzicato effect too weak and directed the string players to use their bows. German's dismay, however, was alleviated to some extent by a compliment from the kindly Sullivan who had attended a performance. The song was published by Chappell & Co. in 1888 and the lyric is included in the script of Broken Hearts published in Original Plays by W. S. Gilbert - second series, by Chatto & Windus [London: 1925 ed.] :-

Far from sin - far from sorrow

Let me stay - let me stay!

From the fear of to-morrow

Far away - far away!

I am weary and shaken,

Let me stay - let me stay,

Till in death I awaken

Far away - far away!

In the summer of 1887, German left the Royal Academy where he had been a sub-professor for over two years and, amongst the jobs that he took at this time, he later recalled that he used to earn two guineas a week playing second violin at the Savoy with seven shillings for matinées.

PRODUCTION

The behind-the-scenes drama of Fallen Fairies rivals that of any of the G & S Savoy operas, with the exception that the resultant production did not prove successful for any of the major participants. The following account detailing the beginnings of the opera and its ultimate unhappy fate is extracted from Hesketh Pearson's biography "Gilbert: His Life and Strife", [Methuen & Co. Ltd.; London: 1957, pp. 248 - 255], supplemented with interpolations from Brian Rees's biography "A Musical Peacemaker: The Life and Work of Sir Edward German" [The Kensal Press; Buckinghamshire: 1986, pp. 146 - 168], which presents the collaboration from German's perspective.

Gilbert's enthusiasm for his blank-verse plays Broken Hearts, Gretchen, Pygmalion and Galatea, The Palace of Truth and The Wicked World was unquenchable, and he determined to make operas out of the last two. He began a libretto of The Wicked World on January 3rd, 1909, and finished it on February 26th, though he was occupied for several more days making improvements. The idea had been in his mind for some time and he had suggested it to Helen Carte in 1897; but her husband did not fancy a chorus 'composed entirely of ladies'. Nor did Arthur Sullivan, Edward Elgar, André Messager, Jules Massenet, Liza Lehmann and Alexander Mackenzie, to all of whom Gilbert proposed the subject. Then, on December 21st, 1908, he wrote to Edward German:

Dear Mr German,

I have conceived the idea of a 3 act Fairy Opera, but the story involves a peculiarity which may stand in the way of its accomplishment. The peculiarity is that the chorus must all be ladies. You will be able to judge whether this would be a delightful novelty or an insuperable difficulty. As I see the piece in my mind's eye it might be productive of exquisitely beautiful effects - but your mind's ear may be altogether opposed to the notion. The story is eminently fanciful - in parts strongly dramatic, with a vein of playful humour running through it. There would be only three men's parts - a dramatic tenor - a vigorous baritone or bass - and a buffo who would be probably a light baritone.

If the idea commends itself to you and if your engagements would permit you to collaborate, I shall be very pleased to go into details.

Yours very truly,

Gilbert's proposal was courteous enough and the opportunity to collaborate with the greatest English librettist would obviously have its attractions. It is clear that German was flattered by the idea of an association. In January, 1909, he wrote to [his sister] Rachel:

Just a line to say that altho' I have had two interviews with WSG I have not written a note of music yet. He is at work on the 1st Act and seems inclined to wait until he has finished it: he will then send it to me. I don't think there is any 'run' in the thing: but I shall of course go through with it, if only for the advt. Of course, nothing must be said about it yet. I'll write you again soon.

The idea commending itself to German, Act I was despatched to him immediately it was finished. The leading part, Selene, was written especially for Nancy McIntosh, and she practised her songs with German, who altogether approved of the choice.

When Sullivan died he left an opera, The Emerald Isle, uncompleted, and it was finished by German, who was the best composer of tuneful airs in England at the beginning of the century, his incidental music for Henry Irving's production of Henry VIII having won great popularity, which was consolidated by his scores for three comic operas: Merrie England (1902), A Princess of Kensington (1903) and Tom Jones (1907). He was not unlike Sullivan in character and attainments: in life, as in music, he loved harmony and shunned discord. His personality and his work appealed to such diverse characters and composers as Elgar, Sullivan, Mackenzie, Parry and Stanford.

But a backer was as necessary as a composer, and Gilbert had some difficulty in finding one. First he offered what he now called Fallen Fairies to Helen Carte 'in virtue of our long association'. But as the offer arrived within a week of the letter in which he had complained that under her management the revivals of the Savoy operas had been insulted, degraded and dragged through the mire, she found the prospect of renewed collaboration unattractive. Next he tried an enterprising American, Charles Frohman, who had produced Peter Pan; then the manager of the Haymarket Theatre, Frederick Harrison; then the lessee of the Prince of Wales's, Frank Curzon, who at first seemed keen, but Gilbert's terms cooled his enthusiasm. Seymour Hicks and Arthur Bourchier were also approached; but the business was settled by C. H. Workman, who had found some backers and wished to produce the Gilbert-German opera. It so happened that Workman's recent performances in the Savoy revivals had influenced Gilbert to write the chief comic part in Fallen Fairies for him.

A month before Workman had formed his syndicate Gilbert was in correspondence with Helen Carte about the Savoy operas not recently revived by her, which would be done by Workman after the new piece. He intended to make considerable changes in some libretti, small alterations in the others:

16 Apl. 1909

Dear Mrs Carte

The only suggestion I have to make arises out of your last letter in which you suggest that if you decide to produce, on tour, any of the operas that are not on your repertoire, after they have been produced in London, you shall be entitled to have the use of any alterations I may make or authorize. It occurs to me that in such a case the amounts paid by Bertie Sullivan1 and myself (or by myself alone in the cases of The Mountebanks and His Excellency) should be returned to us - as (1) it would be the success of the piece in London that would prompt you to add it to your repertoire and (2) the alterations would probably be very material, especially in Ruddigore, Utopia Limited and The Grand Duke.

I do not make this a condition, as I rely upon your being appealed to by its reasonableness.

Yours truly

1 Sir Arthur's nephew and legatee.

Dear Mrs Carte

I accept the terms contained in your letter of the 20th Inst. It is understood that the understanding does not apply to slight verbal alterations - which you will be at liberty to use if you think proper to do so.

Yours very truly

Workman's syndicate wished to have some influence over the class of goods in which they were investing, but Gilbert refused to let them judge the merits of his work and insisted that Workman alone should make the decision. As a rule actors are not good men of business; the exceptions are not good actors. Workman, new to the job of management, had to steer a tricky course between the autocracy of Gilbert and the plutocracy of his backers. He halted between two viewpoints, eventually favoured the men who provided the money, and soon heard from the man who provided the brains:

3 June 1909

Dear WorkmanYour letter has caused me inexpressible surprise and indignation. I told you, a fortnight since, what were the terms I should require for my libretto and referred you to German for the terms he intended to ask for his music. You took no exception to these terms and I regarded that point as settled subject to your approval of the libretto and music. I asked you, a fortnight since, if you were committed to any leading lady and you replied that you had arranged to engage Miss Spain, but only for one production, and that you had a perfectly free hand in that respect with regard to the second and following pieces. I then told you that Mr German and I had agreed that Miss McIntosh would exactly suit the leading part and that the libretto and music had been written with her in view. To all this you made no demur and again I considered these matters as settled subject to your approval of the libretto and music. Having thus, as we supposed, cleared the ground, we took you into our confidence in full, and read you the libretto and played and sung the music to you. You expressed yourself as delighted with both and there appeared to be nothing left to be done but to draft and sign a formal contract. A week after the reading you wrote to offer us ridiculous and insulting terms and inform us that you were bound to Miss Spain for your first three productions (having previously assured me in terms that admit of no misunderstanding that you had engaged her for your first production only), some gentleman who is interested in her having contributed £1000 to your syndicate.

With regard to the terms, I never haggle. They are immutable and must be accepted or rejected en bloc. I have not a word to urge against Miss Spain for parts to which she is suited, but she is wholly unsuited to 'Selene'. Moreover I decline to have my libretto cast by a syndicate.

You have caused us to lose two months in idle negotiations and you have lured us into confiding to you the details of the music and libretto on distinctly false pretences. I decline to have dealings with a man who is capable of such conduct.

Yours truly

Workman decided that the wrath of Gilbert was more to be feared than the threats of Mammon, and duly grovelled. On June 7th Gilbert, opening with a severe reprimand, wrote:

The terms 15 % on the gross receipts are extremely low and cannot be reduced in any way. My 10% is the fee that 1 have always received during the last 35 years, except when I was on sharing terms at the Savoy. It is what I received for The Mountebanks, His Excellency, Utopia Limited (with a guaranteed minimum of £6000 on certain conditions) The Grand Duke, etc. In the case of the two first pieces the per centage was turned into a payment of £5000, with contingencies. In those cases Cellier and Dr Osmond Carr received 5% on gross receipts. On all these pieces I have received 10%. I do not press Miss McIntosh on you. I only say that German and I are completely satisfied with her - that 1 wrote the part for her and German the soprano music. If you can find a better at her salary (£25 a week) we will accept her - but Miss Spain, an excellent soubrette, would be quite out of place in a stately part calling for scenes of passion and denunciation. Miss McIntosh is an admirable singer and accomplished Shakespearian actress, with an individuality and appearance which are exactly what the part calls for.

Please let me know your decision at once as another manager is coming on Friday to hear the piece and music, unless I stop him. The cost of production might have been anything about £2500, but as a matter of fact it should not exceed £600.

Yours very truly,

On July 14th Gilbert was able to advise German that everything had been satisfactorily settled with Workman, who had taken the Savoy Theatre and had 'contrived to get rid of Cellier' - François Cellier, whose behaviour as musical director during Helen Carte's season had riled the librettist. [Gilbert also] informed German: 'I have drafted an agreement in which I have stipulated (inter alia) that you should have absolute control of everything relating to vocal and orchestral matters and that no engagement for principals or chorus should be made without our joint approval.' Having put everything in order, Gilbert left for Wiesbaden, where on October 2nd 'J'ascends dans le ballon.' [Comment from Gilbert's diary, which he kept in French - safe from the prying eyes of servants.] Half-way through the month he returned home and discussed the cast with Workman and German. Relations between Gilbert and Workman, however, plunged from one hazard to another.

Dear Mr German,

We shall be very glad to see you on Monday by the 12.40 from Euston. The difficulty is that Workman asks us to read the piece and play the music to the syndicate that they may determine whether they will or will not produce the piece. To this I have replied that the piece as already been accepted by Workman - that he is under contract to produce it at the Savoy on withdrawal of Mountaineers and that we shall most certainly enforce the terms of that contract.

Unfortunately I have accidentally destroyed the letter in which he accepted the terms embodied in my letter of 6th July. Have you a copy of that letter? If so will you please bring it with you on Monday. Workman says that he can find no such letter among his papers, but that I take to be a clumsy evasion. It is of no great consequence as there is no end of secondary evidence to prove that he has accepted the opera. Anyway it is clear that we can compel him to produce our piece immediately after the Mountaineers. I decline altogether to recognise the existence of the syndicate - who are merely his bankers.

-

Yours truly,

-

W S Gilbert

In his next letter the same mixture of courtesy to German and rumblings against Workman continued. Gilbert had pressed German to make a cut in the Finale because of the difficulty of inventing stage business to fill the time. German, in reply, emphasised the thought which he had given to the work which had occupied him for several months.

In the Finale, I cannot see, if it is to get home, where I can cut it further. This also goes quite fast and to my mind will be most effective. However, I'll still think it over. Speaking generally I think you will find when you come to rehearsal that I have thought out everything very carefully.

The cuts, however, came.

Dear Mr German,

Many thanks for the 'cut' which was suggested, I need hardly say, wholly in reference to the difficulty of filling up the time with appropriate business. I have not yet been able to elicit a distinct avowal from Workman that he unreservedly accepted the terms contained in my letter of 6th July. I have now written to him to say that I will entertain no other matter connected with the piece until I have received a definite yes or no answer to my question.

-

Yours truly,

-

W S Gilbert

German privately had doubts about the length of the run that could be expected. 'It is all artistic,' he wrote to Rachel, 'and the idea is pure Gilbertian, but it is a fairy opera not a comic opera.' He had refused to accept less than five per cent of the gross takings, the original offer, but at one moment he withdrew his request for a guaranteed £250. As usual he was overworking, simultaneously preparing an edition of Tom Jones for use by amateur societies, and matching the final version with the conductor's score. He had been forced by pressure of work to turn down an invitation to write special music for the Welsh National Pageant. A letter from Gilbert on 24th October informed him,

I can get nothing but evasive replies from Workman, - but our case is so clear and so cogent that I have placed the matters in my solicitor's hands as the only means of bringing him to book. I must tell you that the oftener I hear your music the more impressed I am with what appears to be its high technical qualities, its fund of delicate melody and its great variety.

At long last a satisfactory response was elicited from Workman and rehearsals proceeded. In addition to the scoring and supervision of parts for the Savoy, auditions for principals and chorus, delayed by recriminations over the contract, had to be fitted in. Auditions were held at the Savoy; the piece was read by the author to the company on November 8th; and Nancy McIntosh was rehearsed thoroughly at home. Workman did not turn up for the early rehearsals: he was, noted Gilbert, 'toujours malade'; but his particular malady was no doubt auctorphobia, for he did not dare tell Gilbert that one of his backers still wanted the girl he fancied to play the part for which Nancy had been cast.

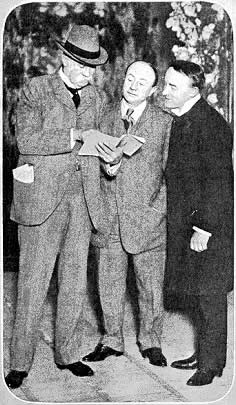

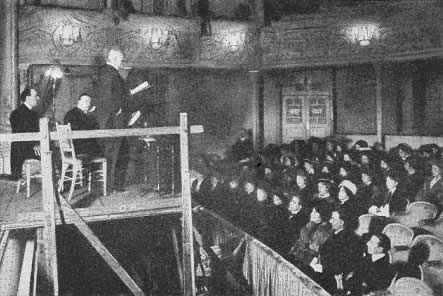

'The long anticipated new comic opera is in rehearsal,' said the 1909 newspaper caption to this photo taken at the first read-through at the Savoy Theatre. On the dais, [left to right], are C. H. Workman [manager of the theatre], Edward German and

Sir W. S. Gilbert. The entire cast of Fallen Fairies is assembled in the stalls.

Workman must have suffered spasms of conscience every time he caught Gilbert's eye, knowing that he had practically promised his backer that Nancy would be relieved of the part at the first possible opportunity. Gilbert lacked the gift of ingratiation which German, like Sullivan, possessed in so eminent a degree, and he was quite incapable of putting people sufficiently at their ease to confide in him. Workman might have explained the awkwardness of his position to a man whose eyes did not see right through him and suspect treachery. As it was, his fear precipitated a catastrophe that might have been averted by careful management and skilful diplomacy.

In any case Gilbert was in no mood to be trifled with after his late experiences at the Savoy. Joseph Harker, who painted the scenery for the opera, described what occurred when the author called to examine it. The warmth of his greeting made Harker wonder whether age had turned the lion into a lamb. But when Gilbert saw the completed scenery, he wanted considerable changes. Harker replied that Gilbert had approved the original designs and that if he wanted them altered he must pay for the work and delay the production. The lion re-emerged and roared for ten minutes. 'I have seldom heard more violent abuse hurled by anyone than that with which Gilbert assailed me on this occasion', related Harker, who then told Gilbert that such behaviour was not to be endured and that he refused to be bullied in such fashion. Gilbert stamped and snorted his way out of the studio, and at the close of the final dress rehearsal before a picked audience publicly stated that everyone except the scene-painter had assisted him loyally. [Harker's uncle John O'Connor had designed the original scene for The Wicked World, the play from which Fallen Fairies was adapted.]

On the first night of Fallen Fairies, December 15th, 1909, Gilbert dined at the Beefsteak Club, spent the rest of the evening in Nancy's dressing-room, and received a 'Belle réception' at the end. He took the stage for applause at the close saying in the course of his speech 'I hope you will agree there is life in the old dog yet.' Early-comers to the theatre had sung Gilbert and Sullivan songs while waiting to encore Gilbert and German. But though the audience was almost hysterically enthusiastic, the critics were by no means unanimous.

REVIEWS

In an interview given to the Daily Sketch the same day, Gilbert had said of the music:"It is extraordinarily beautiful - equal to anything I have ever heard - and quaint when quaintness is necessary." "That must mean,' observed the reporter, that the mantle of Sullivan has fallen upon German, and that the new composer, like the old, sees humour with the same eyes as the author. Granting this we may expect the people to demand more and we may picture Sir William in his great library at Grim's Dyke lying back in his favourite old arm chair to think out fresh fancies and frolics of phrases for the entertainment of countless thousands."

This idyllic scene was not to be realised.

The criticisms were not enthusiastic, possibly because fairyland in Gilbert's verse was quite as carnal as anything in the real world of prose and much sillier. The Daily Mail said, 'The author's hallmark was on all the lyrics....even if it cannot be pretended that he has always sharpened his pencil in this instance to its finest point.' The same critic remarked that Nancy MacIntosh's 'voice is no longer remarkable for its freshness.' [Quoted in Alan Hyman's Sullivan and his Satellites, (Chappell & Co./Elm Tree Books; London: 1978).]

The Pall Mall Gazette praised the opera highly, but the Yorkshire News correspondent remarked that 'the public does not associate homilies with a libretto by Sir William Gilbert, but such are freely provided in the closing scene'. The Observer missed topsy-turvydom: 'It is a strange compound of trifling, and tragedy, of gossamer and gnashings of teeth.... the effect is a little like that of an act of Othello pieced into The Merry Wives of Windsor".' And saddest of all, The Daily Express, after praising the performance, continued, 'But with it all Fallen Fairies belongs to yesterday.'

Like most of the numbers, Nancy's had been encored; her enunciation and that of the entire cast had been praised; her singing was described as fresh, her silvery speaking voice reminiscent of Ellen Terry's, yet several critics commented on her lack of sonority or vocal strength. Sixteen years before, the press had perceived her as an ice-maiden, a girl made of moonlight; now, cast as a fairy queen driven to fury by faithless human love, she found sexuality not in her sphere.

About the scenery reviews were divided: The Daily Mirror thought every-one else was pleased with its art nouveau blossoms and writhings, but for 'Rooty-Tooty' of The Sporting Times, the effect was too red and garish. The Times described it as a gaudy transformation scene. The costumes, however, were delightful. Designed by Percy Anderson, whom Gilbert said surpassed himself, the fairies' headdresses suggested orchids and dragonflies; Nancy wore pale blue, a diamond coronet, and downy wings. Other dresses were spangled with silver or appliqued with iridescent beetle-wing embroidery; great eyes of reddish-purple were painted on the wings of a blue-purple costume." [from Jane W. Stedman, W. S. Gilbert: A classic Victorian & his theatre, (Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1996).]

A week after the opening Gilbert wrote to his collaborator: 'The notices have been rather cruel but I think the piece is more affected by this cursed Christmas season and the coming election than by them. My own opinion as to your music is worth nothing. I can only say that I am delighted with it, throughout, as we all are.'

The critics were divided into those who thought Gilbert's talents were flagging and those who thought the master was still incomparable in the realm of light opera. To modern taste the piece must seem fatally flawed. The heavy accent on the 'vile' nature of mankind grows tedious and has no dramatic strength. German's music too, despite its artistry and thoughtful craftsmanship is not really a vehicle for satire. It has not the swashbuckling vigour of Sullivan, and his characteristic touches of harmony, and rhythmic change, the modulations and extended phrases argue a restraint and delicacy of feeling, at variance with Gilbert's bludgeoning attacks on everything and everyone. There are a few delightful tunes in Fallen Fairies but apart from the Finale to Act I the audience would not have found it easy to go home whistling them. The Overture is definitely sub-standard with a wooden march tune, and throughout the work there is too great reliance upon the old 6/8 jig rhythms.

The truth is that Gilbert's libretto failed to inspire, and also gave his collaborator little chance to develop his potential skills in ensemble writing displayed so finely in the three previous operas, The sweeping melody, "Oh Gallant Gentlemen" is extended to a broad climax at the end of Act I and there is some highly seductive music for three-part female chorus in Act II.

For many an hour

Within her bower

With Ethais philandering

Our excellent Queen

No doubt has been

In roseate dreams meandering.

But elsewhere, solos and duets follow one another at length and in Act II Lutin, has three songs in quick unvaried succession. The fairy music is certainly quite full blooded especially Selene's 'Viennese' waltz "Poor Purblind Wayward Youth", and skillfully avoids comparison with the daintiness of Iolanthe (though no doubt the chorus was divided along the lines unkindly observed some years ago by the critics of Dvorak's Rusalka into 'fat nymphs who sing and thin nymphs who dance'). Yet the score shows no great advance in technique compared with German's earlier work. "Go Then Fair Rose" and the aria for Selene, reintroduced later to bolster up the production, "Love that Rulest in Our Land", are rich and romantic but in the style of earlier work.

Moreover, the association with Gilbert appears to have led to some echoes of the Savoy operas which steal upon the ear; snatches of "Is Life a Boon" from The Yeomen of the Guard and "Our Great Mikado Virtuous Man". Nor would it have been possible to set lyrics such as "When a Knight Loves Ladye" without evoking memories of half a dozen settings of similar lines by Sullivan. Although before the opening the press gave great attention to Gilbert's inexhaustible vigour ('the brightest brained man of his day,' said The Sketch) and prophesied a new series from the partnership, not only were their talents less complementary than those of the old partnership, the dreamy softness of German's music cloaking rather than accentuating the satire, but the composer's cultivated self-effacement precluded demands for the concerted romantic situations in which he excelled. Though, as he had said to Rachel, he had accepted the invitation for reasons of prestige, the experience seemed to congeal, temporarily at least, his musical powers and even his personality.

QUARRELS AND DISPUTES

The collapse of Fallen Fairies was made infinitely more disastrous by the quarrels over Nancy McIntosh, in which both sides tried to enlist German's support. On December 22nd Workman wrote to say that a member of the syndicate did not like Nancy in her part and that she must leave the cast. Gilbert wrote to German to say that he had been informed that the management wanted another Selene. Although angry, his respect for German modified the tone.

Dear German,

I have just received the enclosed astounding letter from Workman. What it means I cannot guess - but I expect it is actuated by an intention on the part of the directors to strike at me through Miss McIntosh Is it your opinion - tell me quite frankly - that their act in inflicting this unparalleled outrage on her reputation as an artist is in any way justified? To take her out of the part and place another lady in it would inflict infinite damage on the piece - for it would be at least ten days before another lady could be got ready. I am practically in your hands. If you think Miss McIntosh should give up the part she shall do so - and pray believe that, if you so decide, both she and I will accept your decision without the smallest feeling of resentment, as I know you are absolutely fair minded and the best possible judge of what is best, really, for the piece. Pray be quite frank as I am most anxious that she should not be placed in a false position - and no one - not even an amateur board of directors - can decide this point as authoritatively as yourself.

-

Very truly yours,

-

W S Gilbert

It would not have been in German's nature to desert Nancy at this stage and, despite his long experience of the theatre, he was profoundly distressed by the turn which events had taken.

Dear Sir William,

I return Workman's letter: it has much upset me. You know quite well the admiration I have had throughout for Miss McIntosh and I still doubt, considering all points, if we could get a more artistic exponent of the part. I am not going to pretend that her singing latterly has been quite what I expected - her voice seems of less volume than when she sang at Grim's dyke [sic], but I put it down to overwork or nervousness.

I have now told you quite frankly - as you wished me to do - all I feel. I was so upset when the letter came that I felt I could not reply right away.

-

Yours very truly,

-

Edward German

P.S. I know nothing of the syndicate but as to their wishing to insult you through the medium of Miss McIntosh - surely this could not be!

In fact at one point the syndicate had summoned German and endeavoured to persuade him that the audiences were not satisfied with Nancy and a replacement must be found. The letter he wrote to Gilbert is full of erasures and amendments though he declares that he refused to hear anything against her and would not see or hear another lady. Finally it was crossed out in his copy-book and was presumably never sent, though it shows his hesitations over acquainting Gilbert with the strength of the opposition. Gilbert was sufficiently pleased, however, with the letter he received.

Dear German,

Your very kind letter is just such a letter as my experience of you led me to expect. I quite agree that, owing to the fatigue of rehearsals and also to her being somewhat out of condition, Nancy's voice has not been as full and round as it was before her long and fatiguing rehearsals - but that it is a voice which keeps people out of the theatre is a charge as preposterous as it is insulting. My firm belief is that there are wheels within wheels and that, for some reason unknown to me, the syndicate intend if possible to place a nominee of their own (a Miss Evans, I believe) [Miss Spain was no longer mentioned and Miss Amy Evans was the new candidate of the syndicate] in Nancy's place. Workman actually stated that Nancy sang out of tune - a thing that I believe she never did in her life - and this by itself is sufficient to show the animus by which they are actuated.

She is staying in town and knows nothing about the syndicate's intention. I shall see her tomorrow and shall have to break the news to her. I am desperately afraid of the effect that it will have on her sensitive temperament and I expect she will be quite unable to play and sing on Monday. She will do so if she can but I have warned Workman to get her understudy ready. What course she will eventually take - whether she will insist on the terms of her engagement (which is for the 'run') or whether she will save her face by a plea of ill health and necessity for rest I do not know.

-

Very sincerely yours,

-

W S Gilbert

This was the first time Gilbert has signed 'very sincerely'. The old man's emotions were heavily engaged.

He demanded an interview with the hapless Workman, who had become entangled in promises to all parties. Gilbert went to see Workman, who must have had such a trying interview that his attitude stiffened; and Gilbert broke the news to Nancy, who received it with fortitude. In order to buttress his shaky position, Workman reported that at one performance nine people had left the theatre in protest. Gilbert replied: 'If, as you told me on the telephone, nine people rose from the stalls during her final scene and left the theatre in disgust (which I do not for a moment believe) it was because you sent them there to do so.' He said there was overwhelming evidence that Nancy had been magnificent in her part and had aroused more enthusiasm than Workman himself or anyone else:

In short, I am firmly convinced that, to serve some ulterior end of your own, you have wilfully and deliberately concocted this utterly unfounded charge - intended to oust her from a part to which, in the opinion of both author and composer, she is exceptionally well suited. It is on that assumption that I shall rest such proceedings as I may be advised to take.

He then resorted to that embodiment of excellence, the law, addressing Workman:

27 Dec. 1909

Sir,

This is to give you notice that I intend to apply today to a Judge in Chambers for an ex parte injunction restraining you from playing Fallen Fairies this evening except with Miss McIntosh or her accredited understudy Miss Venning in the part of Selene. I give you this notice that you may be in a position to face the contingency.

I am yours, &c.

But his solicitor Birkett said that he could not obtain a writ that day (Monday) because it was a Bank Holiday. On the same day he wrote to German:

Dear German,

I have consulted my solicitor and he strongly advises us to apply to a judge in Chambers, next Wednesday, for an injunction to prevent Workman from allowing anyone but Miss McIntosh or her understudy to play Selene in accordance with the terms of his agreement with us and with her. It will be necessary that you and I should make a joint affidavit to the effect that by our respective agreements, no one is to play in the opera without our joint approval and that we are quite satisfied that Miss McIntosh and no other should play the part.

If you will join me in this I shall be much obliged. I propose, unless I hear from you to the contrary, to call for you at Hall Rd at eleven on Wednesday - that we may proceed together to my solicitor's office in Lincoln's Inn.

-

Yours truly,

-

W S Gilbert

At first German hoped that Nancy could resume her role but Gilbert next day swept this suggestion aside:

I find it would be useless to apply for an order compelling the Savoy management to reinstate Nancy McIntosh as she is so sadly affected by her infamous treatment she would be physically unable to take her part again, even though the court decided in her favour. Nevertheless, I will call upon you tomorrow at eleven to talk over the state of affairs and will take my chance of finding you at home.

German sent the following reply to Gilbert on the 28th:

5 Hall Road,

St. John's Wood, N.W.

Dear Sir William,

Yes, I will go with you to your Solicitors tomorrow morning as you suggest, but I cannot, as you know, conscientiously say to him that the singing of Miss McIntosh has quite come up to my expectations. Her artistic attributes generally are so strong that I am prepared to sign an affidavit to the effect that we are satisfied that she should play the part.

-

Yours very truly,

-

EG

P.S. I must add that the action of the syndicate in dismissing Miss McIntosh as they did is intolerable, and of course violates our contract with them.

[Letter quoted in Alan Hyman, Sullivan and his Satellites.]

Perhaps the tacit but real reason, syndicate machinations aside, for removing Nancy McIntosh from the role of Selene lay in her incapacity to project sexuality. Her Fairy Queen was too much a tragedy queen, a reviewer said, and Rolanda Ronald, a young chorus member, described her many years later as lacking any 'star' quality, a spinster who would never attract a man." [(letter to the author, 17 Oct. 1969: JWS.) - from Jane W. Stedman, W. S. Gilbert: A classic Victorian & his theatre].

On the 29th Gilbert took German in a taxi to see Birkett. German was most unhappy to be embroiled in this backstage warfare, and shrank from the thought of court appearances. His situation was an unenviable one. As he had been so keen to have the association with Gilbert, and as he had help and co-operation from Nancy McIntosh he should probably have lent his weight to their cause. On the other hand, he had always had reservations about the singer's prowess, he was aware of Gilbert's power to stir up animosities, he hated any unconventional publicity, he did not live in the rich baronial style that Gilbert adopted at Grim's Dyke, and he might well have feared that a lawsuit could be lost, for the courts might decide that the management had been deceived as to the adequacy of the performer. That would be an expensive matter and would frighten off London managements from putting on his work in the future. His irresolution offended his partner. Gilbert recorded in his diary: 'German joue le fainéant, et ne désire pas se mêler avec un procès. Alors l'affaire est terminé.' But the fact that German played the 'fainéant' did not lessen Gilbert's energy.

Relations were not helped by an erroneous report in the press that the Savoy were planning to follow Fallen Fairies with The Emerald Isle. German denied the rumour and Gilbert accepted his statement, with grace.

Dear German,

Thank you very much for your kind and explicit reply to my rather impertinent question. The fact is that the syndicate seem to think that they have the right to revive Ruddigore after Fallen Fairies - a position which I dispute and I am indeed negotiating with another management for its production. If they had contemplated the production of one of your operas, it would have shown me that they had abandoned their claim on Ruddigore. As it is I am sorry that the report is erroneous and I hope for your sake they may decide to follow FF with the piece of yours.

-

Yours truly,

-

W S Gilbert

Fresh difficulties arose over the inclusion of Selene's aria,"Oh Love that Rulest in Our Land" as Gilbert had no wish to enhance the role of new Selene. He wrote,

I would much rather (it) were not reinstated. It was cut out not because Miss McIntosh couldn't sing it (for in those days you expressed the highest opinion of her vocal abilities) but because it was redundant and stopped the progress of the piece - and also because I did not like the words. As a substitute I wrote the duet for Selene and Ethais . . . I am sure you will see the matter from my point of view. Moreover, both Miss McIntosh and I are bringing actions against the company for breach of contract (my case is now with counsel) and the fact that a song was cut out when Miss McIntosh was to have sung it and reinstated for Miss Evans would be an [word blotted out - imputation?] against Miss McIntosh that an unscrupulous syndicate would not hesitate to employ.

German's reply was conciliatory, not to say apologetic:

Dear Sir W,

I have read your letter and as to the song in Act II the idea was suggested to me by Mr MacCunn and I agreed that it might be desirable. I had not thought of it from your point of view. Therefore I shall now do nothing further.

As you know my aversion to all legal contentions I am very sorry to hear of probable trouble of that kind.

-

Yours sincerely,

-

EG

It is true that Gilbert had made further efforts to persuade German to join him in legal proceedings but he had not succeeded, and the composer's soothing comments were now turned against him. German had written that he was satisfied with Nancy in the part and that the action of the syndicate in dismissing her was 'intolerable and of course violates our contract with them'. Gilbert reminded him of this:

I am sorry you disapprove of my resorting to law proceedings..... I must tell you frankly that I have no alternative but to pin you down to the terms of the two letters I have quoted ..... You will no doubt remember that when we were on our way to Birkett's you said to me 'Miss McIntosh sang magnificently on this final night.' I replied 'You really think that?' and you answered 'Yes, she sang magnificently.'

To complicate matters further, German now had Hamish MacCunn, the conductor, urging him to stand firm over the integrity of his score, without regard to Gilbert's wishes. As for the latter, the onset of the legal case had begun to stir his pugnacious feelings and his letters were more violent in tone. His recollections of the taxi conversation were preceded by a passage of rich invective:

I am sorry you disapprove of my resorting to law proceedings but I think if you had been subjected to a similar outrage to that which has been inflicted upon me - that is to say, if some lady without the ghost of a voice and who had never even attempted to sing a note, had been told off in defiance of all contracts to sing your excellent music, even your dislike of legal proceedings would have yielded to indignation. You bear it quietly because you get a more powerful and full voiced (though not a more artistic) singer than Miss McIntosh - I indignantly resent the syndicate's action in employing a lady to deal with my most carefully written and most difficult libretto who has never spoken a word on the stage before and who is utterly incompetent even to deliver a message - whose acting, in short, is beneath contempt.

German endeavoured to defend himself but his misery is evident in his letters as this, by now daily, exchange, proceeded.

Dear Sir William,

I am very grieved to receive your letter. I don't know that I can say anything more except that I never said that Miss McIntosh sang 'magnificently' on the first night. As far as I remember it was you who used the words. I have said all along that her performance was splendid, and it was, considering the nervous strain through which she was going. This is all very distressing to me and nothing would make me happier than to be able to give her singing unqualified praise.

Gilbert, however, had only so far been using the lighter weapons in his armoury. A heavier bombardment came when he received a suggestion from German that he should audition a particular singer as Darine, for Maidie Hope had also left the company.

Dear German,

No I will not concern myself in any way with the Savoy. If you had supported me, we could easily have swept the floor with that gang of ruffians - as it is I am left to fight alone. I wish to God that the piece were finally withdrawn. Nothing would give me great pleasure than to know that its last hour had come. Let Miss Hilda Morris or anyone else play Darine; the librettist doesn't count.

-

Yours truly,

-

W S Gilbert

Unable, without the support of his collaborator, to institute proceedings to stop the performance, Gilbert brought an action on Nancy's behalf for breach of contract, and on January 13th, 1910, he was able to act solely on his own behalf, sending a note to Workman:

Sir

I write to confirm my telegram of this afternoon - 'I forbid you to introduce into Fallen Fairies a song that has not been authorized by me. Gilbert.'

I shall apply tomorrow for an injunction.

German was now coping with two difficult issues. The first was the inclusion of Selene's aria which Gilbert wished to remain unheard. On receipt of the latter's demand German had obligingly wired MacCunn, who was rehearsing it, to stop the performance, and had also informed Workman by telephone that he acquiesced in the author's wishes. As could have been foreseen this brought a vehement counter-attack from the outspoken MacCunn. He had already sought to make German defend his own interests in a letter of the 13th January.

My dear Edward,

Workman has shown me a telegram from Gilbert prohibiting the use of the song in Act 2. That is, he prohibits it unless it be 'authorised' by him. Now what must be done in the matter is this. You can quite reasonably suggest to Gilbert that he revert to his original construction, reinstate the song and omit the duet!

He told you that the duet was written in place of the song didn't he? Well, the duet isn't much of a success with the public; whereas last night the house not only applauded but cheered the song, and double encored it - I didn't take the second encore, as Miss Evans was evidently and quite naturally, pretty excited and tired.

I am convinced that the retention of this song in the piece is, as things now stand, our only chance of avoiding an untimely closure. Therefore, dear boy do see the man, and if necessary 'entreat' him, as the Scripture says.

Surely he must have more regard for your interests than deliberately to allow the piece to peter out.

-

Thine,

-

Hamish

At 11.30 the same evening, MacCunn again penned a note:

My dear Edward,

I have just heard from Ward, per phone, that the song was done tonight - and that it again secured a double encore. It is our last hope. I left the theatre about 9.30. Harry conducted as I am feeling rather seedy. Indeed, if all this damned nonsense continues I am afraid I can be of no further active use in the matter.

I would do anything I possibly could for your sake old boy, but all this agitato business is getting on my nerves;

- Hamish

Marginally emboldened by this German did approach 'the old man' with a request that the song be included. 'Considering the many months work I have put into the opera, and that every little is a help to the possibility of making the piece run I wonder if you would reconsider your decision and allow it to be reinstated?' Gilbert's first reaction was entirely negative:

Dear German,

No consideration will induce me to consent to any alteration whatsoever in the libretto. I am now engaged in applying for an injunction.

Later on the following actions will be brought against Workman personally:

Gilbert v Workman - Breach of Contract

McIntosh v Workman - Slander and Wrongful dismissal.

At the same time as he was making efforts to salvage the song, German also had to contend with efforts made by Gilbert to embroil him in the impending actions over Nancy's capabilities. He had written another letter on the 13th.

Dear Sir William,

I shall not feel comfortable until I have told you that one thing in your last letter hurt me. It is that you do not seem to realise the admiration I have for your libretto. From the moment you approached me in regard to giving it a musical setting I have been quite ingenuous. I have tried to show you the pleasure - indeed the honour - I felt at being associated with you.

On one point only have we come into conflict. When you pressed me to pronounce on Miss McIntosh's singing in the theatre (and you added that you would have not the least resentment to my plain speaking) I could not conscientiously give it unqualified praise. Much as I admired her artistic attributes I was placed in a very delicate position as our correspondence will show.

For the rest time will prove all things and whatever happens I shall always feel proud at having been associated with your fine libretto.

- Yours very truly,

- Edward German

P. S. You say you are going to pin me to my letter of December 22nd and 28th. I think it will be better for me to show the whole of our correspondence since Dec 22nd (when you wrote enclosing the letter from Workman). This will give you some idea of the delicate position in which I was placed when sending my replies to you.

By this time Fallen Fairies was a doomed enterprise. MacCunn wrote again to German three days later on 16th January, 1910 with some venom:

My dear Edward,

I suppose that you have heard that the 'notice' is up on the call board terminating the run of Fallen Fairies in a fortnight. My sympathies are with you in the whole wretched and unhappy history of the piece up to now.

And I can't help saying that I think Gilbert has acted or is acting in a manner so contemptuous of you and the deservedly high place you occupy in the musical world of this country.

On the occasion of his speech after the first night he spoke of there being 'life in the old dog yet'. The sort of life he exhibits as an unwholesome old hound is not edifying. Why don't you put your foot down and insist upon your song being sung and so secure to the piece a sporting chance?

When Gilbert heard of the threatened closure, and the management's desire to attribute failure to his suppression of the most applauded song, he relented to a small degree, declared that he would be distressed at being the means of throwing eighty people out of work and agreed to the inclusion of the inaptly named "Oh Love that Rulest in Our Land" if Workman would apologise for using it without permission and pay certain costs. German thanked him for his 'kind and considerate' letter and urged Workman to accept the terms, which he did. Gilbert replied civilly that he had been guided by consideration for the composer's interests which he would be sorry to imperil, adding 'At the same time I cannot allow Workman and his precious syndicate to twist my tall with impunity.' Gilbert took the well-known actor Cyril Maude and the famous dramatist Arthur Pinero to see his solicitor in support of his affidavit.

The production closed on the 29th Jan. The receipts were low according to Workman, there were only £16 of bookings spread over several weeks, and the only life-line that Workman could offer was a promise to continue if Gilbert and German would guarantee him against loss. It appears that German did make some gesture of assistance but there was little chance of the begging bowl being replenished in Eaton Square, from where Gilbert wrote on the 30th:

Dear German,

As I wired to you I will most certainly not guarantee that syndicate of rogues and fools against loss. They have paid me nothing since Jan.1 and of course will pay nothing. A piece treated as that piece has been must necessarily go to pieces and from my point of view the sooner the better, for, as it is, my libretto is held up to ridicule and contempt every time it is played.

I have today commenced my action against Workman for breach of contract.

P. S. If you had joined with me in applying for an injunction to restrain them from substituting Miss Evans for Miss McIntosh, I believe the piece would now be running to £200 houses. The libretto really counts for something.

German's unhappiness was the more intense as his critics had a measure of justice in their case, however intemperately Gilbert may have expressed himself. If he had had doubts about Nancy McIntosh the moment to stress them was during the audition period when he was allowed a large share in the musical decisions. No doubt her closeness to the Gilbert household would have made this embarrassing, but she deserved the support of those who had selected her. A touch of the scrupulous exactitude of his mother comes into the correspondence where he qualifies his praise and makes reservations. If the soprano were in truth ruining the production however, then better methods of making a change could have been employed than those which the syndicate chose. MacCunn's position was the correct one. German was a composer of national renown, and should have defended the retention of Selene's aria which had been with considerable labour scored and rehearsed and proved popular.

Neither space nor probably the reader's patience would admit a complete record of the long rumblings and explosions that followed the failure at the Savoy. Gilbert demanded another affidavit to the effect that both men had contracted with Workman and not with the syndicate. 'Although Workman is a man of straw he can nevertheless command a salary upon which, or a portion of which, we can make a claim.' German's refusal, led to reiterated attacks in which he was by now saddled with responsibility for the full debacle: 'If you had joined with me in applying for an injunction against putting a lady in the part who had never spoken a line upon the stage the piece would have been running merrily at the present moment - but your abstention caused the bottom to be knocked out of the opera and it sunk at once.'

Eventually proceedings came to a close. Nancy McIntosh, too, was appalled at the prospect of facing cross-examination in court and German wrote with some firmness to say that he would have to state in evidence that he knew of the existence of the syndicate and believed Workman to be acting for them rather than in his own private capacity. Nancy had engagements in Vienna and Budapest which she could not cancel and would therefore not be present when her case was heard. Although he rebuked German for accepting a lower royalty to help out the management ('I am sorry you consented to reduce your very moderate royalty. He knew better than to ask me to do anything of the kind') Gilbert stopped the actions, leaving Workman and his backers to pay the costs.} He never forgave Workman for his slippery conduct, and refused to let him revive any of the Savoy operas. Workman had intended to follow Fallen Fairies with Ruddigore, but at the end of 1909 Gilbert asked Malone, manager of the Adelphi Theatre, if he would like to do it. Writing for himself and Herbert Sullivan, the librettist of Ruddigore made a remark that would not have pleased the composer: 'We propose to cut out a good deal of the heavy music in Act 2.'

On May 30th, 1910, Helen Carte asked whether Gilbert wished to resume control of the Savoy operas, her acting rights having lapsed. He replied that 'the bottom has been knocked out of their value for production in London by the circumstances attending their recent revival. Many years must elapse before the operas recover their former prestige.' He therefore had no wish to resume the performing rights, which were again bought by Helen, who paid £5000 for another five years. Before she did so Workman got to hear that the rights were in the market, and begged Herbert Sullivan to obtain Gilbert's permission to let him make an offer for them. Herbert arrived at Grim's Dyke with the actor's proposition on June 22nd, 1910. Gilbert did not keep Workman in suspense, writing on the same day:

Sir

Mr Herbert Sullivan has shown me your letter re Savoy operas. I do not intend to waste any epithets upon you - you can easily supply them yourself. It is enough to say that no consideration of any kind would induce me to have dealings with a man of your stamp.

I am, &c.

It was the last roar of the old lion, though he emitted an occasional growl almost to the end.

The re-burgeoning of the Savoy tradition was not to be. In February, 1910, German had written to Rachel, 'Gilbert's actions may come on at any time. He is an awful old warrior and I have quite done with him so far as writing another opera is concerned.' Before his death Gilbert wrote only one dramatic piece, The Hooligan, produced in 1911 on the joyless theme of a prisoner in the condemned cell who dies of heart failure when he learns of his reprieve. He did not follow up his acquaintance with German and continued to hold him responsible for the doom which had befallen Fallen Fairies. The experiences German suffered as a result of his association with Gilbert and the signal failure of the work terminated his involvement with opera. He never again wrote a new work for the stage.

Page modified August 2, 2011