|

|

||||||

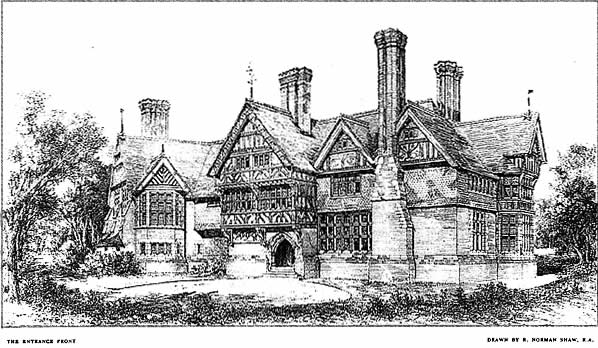

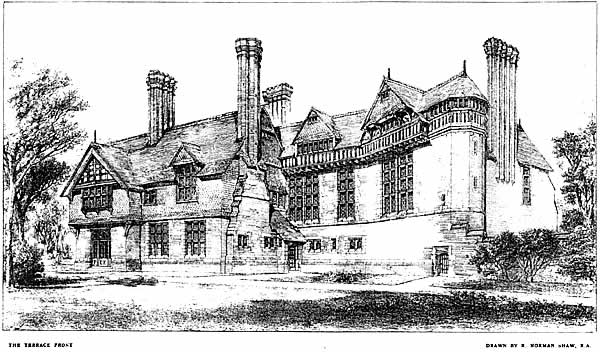

GRIM’S DYKE HARROW WEALD THE RESIDENCE OF MR W S GILBERT

– R NORMAN SHAW RA ARCHITECT

"Grim’s Dyke." Architecture 2 (1897) 355-368.

There stretches out, on the northern borders of Middlesex, remote from the suburban part of London, although only twelve miles removed from the stress and turmoil of its streets, as fair and fertile an expanse of country as these islands can shew. The rich and park-like scenery of Harrow Weald has not yet come within the clutches of the builder of more or less desirable villa residences, and on a golden afternoon of late July, when the scent of the hay is fragrant in all the meadows roundabout, it is possible, like another exploring Columbus, "silent upon a peale in Darien," [sic] to ascend the uplands which run parallel with the borders of Middlesex and Hertfordshire, to gaze out over the fertile meads and woody parks, and, with the exception of Harrow seated in majesty upon its hill, to discover, within the circuit of your gaze, none of the habitations of man. This lovely wealden district, comparable in beauty and fertility, if not in extent, with the Weald of Kent, is bounded to the east and west by Hendon and Pinner, to the south by the rising ground about Sudbury and Northolt, and to the north by the old-world village of Great Stanmore and the high ground through which runs that ancient fosse known as Grim's Dyke.

|

|

| Across the Moat | Photo by the Editor |

Here, where the Dyke wends its way past the tall bracken of Harrow Weald Common, and through the tangled coppices of pines and oaks and the graceful silver birch, Norman Shaw built, in 1870, a fine house for Frederick Goodall, the Royal Academician. One does not know by what fortunate circumstance the painter became acquainted with this breezy upland, whose bracing yet soft atmosphere is not the least of its charms, but certainly the scenery and the rustic cottages scattered here and there by the roadside are eminently paintable, and little "bits" in the turn of the road, or by the untouched selvedge of the Common, recall the fine free canvases of Morland and Gainsborough, if not also those grand breezy pictures of David Cox and Old Crome. Materials for a Morland exist within eye-shot of the lodge which guards the carriage drive to Grim's Dyke, in the roadside inn whose quaint sign, the "Case is Altered," is supported on a tall post mid embowering trees, and the rustic waggoners' [sic] carouse by the benches outside the threshold, just as they did when that dissolute genius settled a tavern score with a sketch, a hundred years ago.

It was when Norman Shaw's reputation was still in the making that Grim's Dyke was built, and it remained still for that artist among Architects to prove what he had set out to prove, that old English Architecture, from the time of Queen Elizabeth downwards, was not really, as so many had apparently imagined, incompatible with modern ideas of comfort. At that time, twenty-seven years ago, the Gothic revivalists who had attempted to force their convictions upon the age had begun to suffer from their own extravagances. They were enthusiasts for Gothics and Purists, and would abate no jot of their purely antiquarian enthusiasm in order to render habitations the more habitable. They had, in fact, the ecclesiastical warp which ran through all their doings, and clients in those days had to accept Gothic in every conceivable form.

The genius of Mr. Norman Shaw is distinctly eclectic. He has, in the course of his long and brilliant career, studied the best wherever he has found it in the works of the old men, and in doing so has assuaged the angularity and abated the harsh treatment which distinguish much of it. There is, perhaps, no sorrow more poignant than that of the man who, gifted with artistic sensibility and blessed in the possession of an old English home, finds that home, for all his delights in the beauty of mellowed brick and lichened stone, practically uninhabitable. Try though he may, he cannot be comfortable there, and, in the end, he begins—quite unreasonably—to suspect his artistic sympathy an affectation and himself something of a humbug. His sympathies and reverence for the old work forbid his laying hands upon it, and yet it is abundantly patent to him that those low-browed passages, those insufficiently fenestrated rooms, might with advantage be altered to suit modern ideas. Walls built, centuries since, four or five feet thick for security, are quite three feet too deep for the householder who pays his rates and taxes and puts his trust in providence and the police. When there were no police and Might was Right, men could endure the darkling rooms which were the outcome of windows few and small, and of walls along whose deep embrasures the light of heaven exhausted itself.

At Grim’s Dyke, as elsewhere "all along the line," Mr. Norman Shaw’s fine perceptions merit the earnest study and the admiration of our time. No need to appeal for appreciation of his work, for it has long since won the highest possible praise and earned that most honest of all recognition, the consistent—and yet inconsistent—following of the lead he has created. The artistic salvation of domestic work was to be gained in other ways than that of slavishly copying any particular period, and to this discovery we owe the Architect of Grim’s Dyke the inestimable blessing, among others, of the extermination of the "Italian villa."

Just how much this means you may see who wander to the portals of Mr. Gilbert’s lovely house; for, not so far away from it is one of those egregious habitations, built of honest stock brick, with a dishonest coating of stucco, aping the fine building-stone or the marble of an Italian villa on the shores of Lake Como or Maggiore.

The estate on which the house of Grim’s Dyke is built extends to a hundred and ten acres of mixed woodland, garden and farm-land. The approach from the highway is guarded by a gabled red-brick and timbered lodge, and goes, in something like a quarter of a mile of curving carriage drive, through plantations of pines and silver birches, to the house which, curiously situated in a slight depression on this commanding upland, with its surrounding trees, commands no view and is thoroughly masked from the outer world. From the lodge the eye ranges to Harrow, whose needle-spire soars above its neighbouring elms, four and a half miles away. From this standpoint, so clear is the atmosphere, you can make out the details of the very varied Architecture which crowds upon that scholastic hill. There is the parish church of many periods with chapel of Sir Gilbert Scott’s designing, Burges’ Speech-Room, Cockerell’s additions to the school, and T.G. Jackson’s boarding-house. For the proper identification of all these it may be conceded that the Eye of Faith is necessary, but it is quite possible to recognise a design of Scott’s as far as sight carries, which may or may not be an admiring criticism.

It is easy to see what considerations weighed with Norman Shaw when he tucked away the house of Grim’s Dyke behind the coppice, and in a fold of the hill which shuts off this grand panorama from the view. He wanted to bring the Dyke itself, and the terraces that would spring from it, into the composition, and although no sign of this is given in the original sketch, we know a man by his work, and this is not the only instance by many that Mr. Shaw has evidenced the enormous value of "site" to the artistry of an architect’s creation. At any rate, Mr. Gilbert’s criticism on the selection is shrewd and incisive. It will be seen that he approves the isolation and the curtailed outlook. "It is a grand scene over Harrow Weald, and, like one’s first glimpse of the Alps, commands admiration. You say, "How magnificent!" and think you could look at it all day and every day; but when you see it the next morning you remark, ‘Ah, there’s that view!’ and the day following, and for ever afterwards, if you were obliged to have it under your windows, you would be bored by it; as it is, I can walk out and see it if I want to." Which is true enough, and quite worthy of the author of the Bab Ballads and the dramatist of many delightful plays cast in that convention which is so peculiar to himself that it has been called "Gilbertian humour."

The near approach is one which would by no means please a nouveau riche, for after leaving the plantations and the bracken behind, the carriage-way dips gently downwards, bringing one to the house by a route which almost convinces you that you have taken the wrong turning and come in by the back way. Suddenly, however, the drive opens out to a broad stretch of gravel and the magnificent gabled front of Grim's Dyke stands on the left hand. The twenty-seven years that have passed since the house was finished have dealt kindly with this mingled work of red-brick, stone and timber. The chief feature of the front, the great timbered gable which projects in two storeys above the porch, has weathered delightfully, house-martins [sic] have built their nests under the eaves, and ivy has grown luxuriantly over the solid brickwork of the ground floor. To the right hand, as you face the house, rise two smaller gables from whose midst a tall clustered chimney stack soars above the roofs. A plain stretch of wall-surface, now ivy grown, gives a strong character to the extreme right angle, while between the projecting chimney-breast and the porch the whole intervening space is occupied by the many-mullioned windows of the hall. Economy with efficiency was the note of Grim's Dyke when Mr. Shaw built it; it still is a legend among Architects that it was for its size one of the cheapest houses its Architect ever put up.

When Mr. Goodall sold it and was succeeded by Mr. Heriot, the new owner spent a considerable sum in beautifying the grounds and extending beyond the kitchen department a large billiard-room, the details of which are lamentably incongruous. Mr. Gilbert, settling here from his town house in Harrington Gardens seven years ago, has since made considerable additions in the way of building new bedrooms over the billiard-room of his predecessor and naturally destroying altogether the "Scale" of the whole domestic quarter. Necessity therefore demanded various rearrangements of the ground floor, which are not even now quite complete. It is difficult to convince the lay mind that it is impossible to double or treble the sleeping capacity of a house without throwing out of gear the administrative department, and although patching and adding and enlarging increases the delightful inconsequence of a country house, it does not--and it cannot--add dignity to the Architectural composition or keep up the "balance of parts," which is the very essence of Architectural congruity. It is not known who designed the billiard-room at Grim's Dyke, and Mr. Gilbert does not even know. It is charitable enough to schedule it as a lost opportunity, but then only Norman Shaw himself should have touched it.

Built in the first instance for an artist, the studio was the first consideration in the planning of the house, and everything else, if not indeed of quite minor consideration, was at least subservient to it. And the plan gives the conviction about the site, for the turning of the axis is logically arrived at and is no mere "trick" for effect. The main part of the house is square with the terrace commanding the Dyke, as seen in the exquisite photograph above, and the mere necessity of the studio being due north and south gives character to the plan which the recent additions have so utterly destroyed. Grim's Dyke was renamed "Graeme's" Dyke until some time after Mr. Gilbert had settled here, when, tired at length of the quite unnecessary and arbitrary variation of a title, he restored the original spelling of that ancient earthwork which runs through the grounds and gives the place its impressive, and, indeed, only possible name. The imagination boggles at Mr. Gilbert, of all men, finding a home in a "Rochlea," "The Laurels," or any other name of obvious suburban mintage, and it was quite to be expected that he would sweep away the affectations in the sham mediaevalism of "Graeme." But when you ask him how the spelling came thus to be altered back to its original form, he says simply that he thought a name of two thousand years' lineage was quite respectable enough for him. At which saying your mind travels back quickly to the anti-Philistine hatred which "Bab" must have for that truly middle-class British adjective, and you find yourself quoting the line from the Sorcerer respecting the "respectable Q.C.," which was alway [sic] irresistible, for are not all Q.C.'s respectable, even as, in the days of chivalry, all knights were brave and ladies fair?

The oriel which, placed beneath its effective gable, looks at an angle upon the drive, as seen here in the architect's drawing, is one of the studio windows; it commands the west, and it was here that Mr. Goodall was wont to sit and paint sunsets.

A flight of five steps leads into the porch, and so, to the right, into the hall, from which, in front, to right and left respectively, entrance is gained to dining-room, study, and to the short flight of stairs which leads along a corridor to the drawing-room. A great model of a three-decker man-o'-war stands by the window of the hall, the masts rising to the ceiling. Sixteen feet in length, it is complete down to the smallest detail of spars and rigging, and was originally made as a model for the set scene which served for the two acts of H.M.S. Pinafore. At that time, however, the bow was not included, and this was added when the revival ended its run at the Savoy Theatre and the model was no longer needed. Over the hall fireplace are three niches filled with fourteenth century alabaster carvings representing the Nativity.

The corridor, through which the backward glance from the drawing-room reveals a long vista of picture-hung walls and richly-carved balusters down into the hall, is always a delightful feature in Norman Shaw's houses. The drawing-room is a dream of beauty, and has doubtless gained in its transition from a studio. An immense and lofty room, its roof is timbered, and something of the kind which they call in the Cornish churches—where its like may be seen—"cradle" or "waggon" roofs. It is, as from its origin one is prepared to find, a very well lighted room, with windows occupying all the available wall-space at either end, and the oriel already referred to in one of its angles. The room is lit at night by a central chandelier made of copper, brass and silvered metal by Strode & Co. Wax candles only are used. This chandelier will be noticed in the accompanying illustration of the room.

The great alabaster chimney-piece was designed by Ernest George, after a sketch supplied by Mr. Gilbert, himself, and exhibits some very fine carving of festooned fruits and flowers, between the terminal female figures which divide the upper part into four panels. The caryatides, two grinning satyrs, are quite unusual, and, a liking for the grotesques being assumed, are very fine of their kind. The whole is a singular design of mingled Early and Late Renaissance feeling, and the alabaster from which it is carved is magnificent. A French sculptor was originally employed upon it, with the result that the female figures were, to put it in a mild way, fleshly, and the whole design under that craftsman's hands bade fair to become a very characteristic example of French Art of the Third Empire period. Mr. Gilbert saw this Palais Royal horror developing before his eyes with disgust, and asked that sculptor if he did not employ a model? "Me!" queried the outraged Frenchman, "I have no need of ye mod-el!"

"Indeed," replied the dramatist, "Michael Angelo would have had a model," and so the irate artist was dispensed with, and the work was given to an English sculptor, whom Mr. Gilbert named to the architects. The result was eminently satisfactory, "but as he only worked three days a week and drank on the other three, I had to allow him eight months instead of four to complete the task," adds Mr. Gilbert, significantly.

The dining-room seems comparatively small after leaving this large apartment and, as hinted before, Mr. Gilbert contemplates enlarging it. Some fine old oak furniture may be seen here, and there is an ingle-nook at one end. The oak sideboard has an interesting history. It was made in 1631 for one Sir Thomas Holt, who in a fury slew his cook. Perhaps Sir Thomas suffered from dyspepsia and the cook was not a cordon bleu. In that case he should not have murdered the man but have made his "punishment fit the crime" by compelling him to partake largely of his own cookery. But he was not a humorist, and as contemporary accounts go, "tooke a cleever and hytt hys cooke with ye same uppon ye hedde, ande so clave hys hedde that one syde thereof felle uppon one of hys shoulders ande ye other syde on ye other shoulder."

Sir Thomas was not convicted of murder, for the argument that the indictment did not specifically charge him with slaying the man although his head was chopped in halves prevailed, and he was acquitted. This proves, as Mr. Gilbert must himself have found, that the Law is an excellent foster-mother of humour.

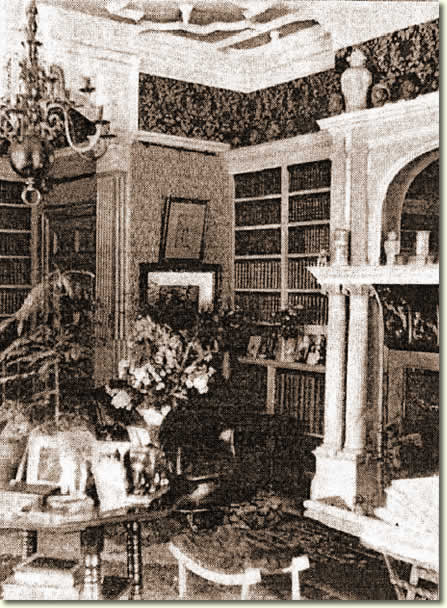

The Library—originally the drawing-room—is now, as the studio was once, the centre of the house. Here Mr. Gilbert works, seated, not at a desk, but in a capacious armchair with a writing pad on his lap.

It is a light, airy, and pleasant room, with a window opening on to the terrace and commanding a view of the formal garden outside and the hillside wildness of the woods beyond, with the two pigeon-houses, between which the white pigeons—"decorative features," Mr. Gilbert calls them—fly in graceful, parabolic flights. A sundial stands in the centre of the patterned flower beds and gives that air of repose and antiquity which is the peculiar property of dials. They need not be old, indeed this one is not. But old or new they argue seventeenth and eighteenth century ease, and generally bear Latin inscriptions, which testify alike to the piety and the learning of our forefathers. There has been a book written about sundials, and the inscriptions on them are collected by quite a number of enthusiasts. Of these was that lady of whom Mr. Gilbert tells a delightful little story.

She was, as she could not choose but be, charmed with the beauty of house and grounds, and the sundial came in as a climax of it all.

"Is that a sundial, Mr. Gilbert?" she asked in an ecstasy. "Is there an inscription on it?"

"Yes," replied the humorist to both her queries.

"May I see it?" and with the accorded permission and a note book she walked over and read on the dial an inscription which certainly was not classical. It merely stated that the same was manufactured by "THE ARMY AND NAVY STORES."

|

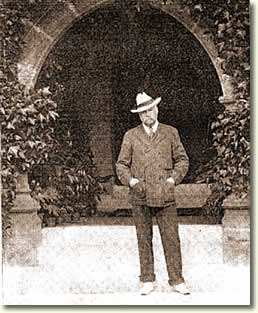

| Mr. Gilbert in the Porch |

The Tennis Court and The Dyke, which, bordered with tall bulrushes, spanned with rustic moss-grown bridges, and bearing on its placid surface rare varieties of water-lilies, resemble very closely the beautiful second set in Patience, painted by Emden, "A Glade" in the grounds of Castle Bunthorne.

Norman Shaw has proved himself here an artist in the use of materials as well as in planning, for in the terrace walls which enclose the Tennis Court, as well as in the bridges, he has used a cunning mixture of red brick, worked stones and unchipped flints laid in irregular courses in thick beds of mortar, the kind of old wall one sees very frequently in Hampshire, that county of flints. Some of the worked stones came from Harrow Church, which was being "restored" while Grim's Dyke was in progress, and fragments of inscriptions peer mysteriously from the bricks and flints, beginning and ending with equal suddenness and perplexing the beholder with queries that cannot now be satisfied.

How finely the gables of the house compose with the Dyke, and with what a grandly "built-up" aspect the Architect has endowed the front, as seen from the Tennis Court, the illustrations to this article may sufficiently well prove. Nature, too, has done wonders in the twenty-seven years since the building was done, the gardens trimmed out of the wild uplands, the plantations set, and the Dyke broadened out. It is a romantic relic of a bye-gone order of things, this great earthwork, with its fosse and corresponding vallum, the fosse filled now with water from land-springs and the vallum thickly overgrown with trees. Twenty centuries ago, its course through Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire defined the bounds of the kingdom of Cassivellaunus. It went quite regardless of natural features, pursuing its course up hill and down dale, and was not so much what Lord Beaconsfield, in speaking of the mountain ranges which separate India from Afghanistan, called a "scientific frontier," as a purely military and arbitrary dividing-line between the dominions of antagonistic British kinglets. Who "Grim" was whose name attaches to it, let antiquarians decide, but certain it is that Death, sudden and terrible, lurked in the shadow of the Dyke when it was maintained as a military work, and intercourse between the nations—or rather shall we say the tribes?—was forbidden. That these Dykes, which occur frequently in the Marshlands between the territories of the varied tribes which once occupied these islands, were ever effective precautions against invasions of territory, has been gravely doubted by antiquarians. It must not be lost sight of, however, that these barriers, set between tribes and races consumed with a lively hatred of one another, were primarily designed, not to prevent invasions so much as to check the petty border forays that harassed and unsettled the frontiers, and usually resolved themselves into nothing more serious than the raiding of cattle by small bands, and the pillaging of homesteads.

|

|

| In the "Den" | Photo by the Editor |

| Formerly the Drawing Room. The Mantlepiece is not by Mr. Norman Shaw, R.A. | |

We may concede that an army of invasion would have experienced little difficulty in overpassing the Dyke, but to marauders returning from a foray, laden with spoils and encumbered with the cattle they had driven off, it must have proved a serious obstacle. Plunder might be taken across without much delay, but the raided flocks and herds, which in those days when manufactures were not dreamt of, and every man was either an agriculturist or warrior, and, at a pinch, both, formed the wealth of nations, were not so readily driven across mounds and deep ditches. To leave the cattle behind would be to fail in the foremost object of their raid; to remain meant certain death at the hands of the pursuers.

The average height of the remaining portion of the vallum of Grim’s Dyke (and long stretches of it have been ploughed level) may be put at ten feet, while the ditch has a depth of six and a width of twelve feet, and thus it may readily be imagined that when it was built it was a really formidable bulwark. Its purpose has passed away now for many centuries, and it serves at the present day to give a grateful touch of old-world mysticism to a house and gardens but a generation old.

A curious relic of old London may be seen here, standing in midst of these quiet waters, and green with the moisture dropping from the overhanging trees. This is the contemporary statue of Charles the Second from the garden of Soho Square, where it stood ever since the days of the Merry Monarch (when the place was called King Square) until twenty-five years since, when Mr. Blackwell, an enterprising London merchant, presented it and its battered pedestal to Mr. Frederick Goodall. The statue is carved in stone, in the extraordinary classical convention that obtained throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and even penetrated into the first quarter of the nineteenth, impelling our sculptors to robe kings, statesmen, heroes and engineers in Roman togas which they never wore, and would, very properly too, have been ashamed to wear. So, thus we see Charles in a flowing wig, armour, sandalled feet, and a long, long robe falling from his shoulders. One wonders if this whimsical statue, with its odd mixture of the costume of the fifth century and the sixteenth, gave Mr. Gilbert the idea for the grotesque dress provided for Mr. Barrington in the second act of the Grand Duke? or whether it suggested the statue of the Regent in His Excellency?

Of one thing we may be certain; that Mr. Gilbert might to advantage teach Architects a very great deal of the art of landscape gardening. One can imagine what Grim’s Dyke would have been in the hands of a modern Philistine, who would smother the terraces with statuary and bring "sanitary science" to bear upon the water-ways of the Dyke itself. Rarely in modern Architecture, and in modern landscape gardening, do we find poor old Nature getting a chance to assert itself. The lawns at Harrow are as trim, as soft, as even, and as velvety as any in the county, but the borders are rich in the handiwork of nature, and only repressed by the hand of man when the very luxuriance of its growth would otherwise run away with its discretion.

Those of us who know the author of Patience may know how Mr. Gilbert could fall upon the wretched gardener who would dare to trim his hedges with the accuracy of a hairdresser, but then the author of Patience was a stage manager of rare ability, and few who had not the gift of dramatic, or rather stage effect, could well appreciate the delightful scene which the camera of Mr. Gilbert himself has depicted on the next page.

|

|

| A Corner of the Drawing Room | Photo by the Editor |

Again, the fine model of Her Majesty’s Ship "Pinafore," which stands in the hall, is in itself a dramatic touch very valuable on a first entry of Grim’s Dyke. In the grounds one gets a happy and delightful juxtaposition of the wild bracken creeping away from a velvety lawn and running free through the mystery of wood and hillside. None, perhaps, but a Gilbert would have valued so highly the decorative effect of those white pigeons; none but a Gilbert would tolerate the "effect" of rabbits in their wild condition, scuttling across the lawn at the approach of visitors, and few of us know the value of a leaf-flecked gravel-path, as you may see on the slopes of Harrow Weald just when the first days of early autumn are asserting their sovereignty.

The present owner of Grim’s Dyke professes very frankly to be at issue with the eminent Architect of his house over fireplaces, and therefore we find that the mantel in Mr. Gilbert’s own room is not that which Mr. Norman Shaw erected. We are ourselves at issue with Mr. Gilbert over this, but, then, the masterly way in which he himself re-arranged and re-planned the kitchen department almost prompts us to forgive him for this trifling touch of vandalism. On the other hand, the truly magnificent and gorgeous overmantel in the drawing room already spoken of, and which quite equals Mr. Shaw’s very fine example found at Lord Armstrong’s place at Rothbury shows very clearly how truly Mr. Gilbert himself is imbued with artistic perception.

|

|

| The Bathing Cabin and King Charles' Statue in the Grounds | Photo by W. S.Gilbert |

But is it within the proper scope of this article to enlarge upon the delightful fact of this fine house being the work of our foremost Architect, and now the residence of our leading Humorist? Surely it is, and it may be permitted, perhaps, to recount the delight which Mr. Gilbert owns to taking in his house and his beautifully-varied demesne. He generally goes abroad for the winter months, in search of sunshine, "and yet," he says, "I am not happy until I reach home again. I hope, except for holidays, never to leave Grim’s Dyke." For the dramatist, who has lived so long in the full glare of publicity, to leave London and to become, as Mr. Gilbert has done, a gentleman-farmer, may seem a radical change, but that way lies content and peace, and be it said here that Mr. Gilbert lives up to the past, his farm being a model one and conducted on business principles. He is a Justice of the Peace and sits on the Harrow Bench, from which it has been whispered that he delivers judgments of Rhadamanthine severity. But this is something less, or something more, than truth.

|

|

| Mr. Gilbert's "Decorative Features" | Photo by W. S. Gilbert |

Page modified 23 April 2015