|

|

||||||

by John Sands

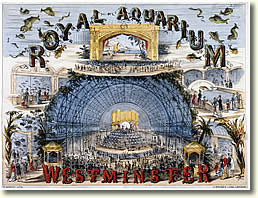

Although the Westminster Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden was one of the most fascinating entertainment venues in late-Victorian London, its history is now all-but forgotten. Arthur Sullivan’s direct involvement in its earliest days was limited to the first half-year of its existence, but his name was significant in attracting publicity for what was (initially at least) intended to be a landmark institution. When Bruce Phillips, Secretary to the Royal Aquarium Summer and Winter Garden Society (Limited) applied for a music and dancing licence in October 1875

“Probably every member of the court knew the site of the building, and remembered it in its former condition of a miserable, unused piece of ground – a receptacle for all kinds of refuse. On that site a magnificent and splendid structure had been erected by the Society now applying for the licence. […] It had been found that visitors to other Aquariums liked to have other amusements as well as observing the fish. The directors had therefore determined to have a botanical display and there would be a Summer and Winter garden. […] The old reproach of foreigners against the English people that they did not appreciate music was no longer applicable, and we are now a musical people. To gratify this growing taste on the part of the public, the directors were organizing at great expense a large band of skilful and able musicians, and Mr. Arthur Sullivan, the eminent composer, was to have the direction of all the musical arrangements. […] No lady unaccompanied by a gentleman would be admitted after dusk.” (The Times, 9th October 1875)

In view of the later history of the Aquarium, this last sentence ought to be noted, as should another observation made at the 1875 hearing:

“Mr. Grain of the Westminster School authorities said that this was simply and entirely a commercial enterprise, disguised under professions of a desire to cultivate musical and artistic tastes among the people. Its first object, however, would be the production of a good dividend, and this being so, the Bench, as men of the world, would easily see what would be likely to happen if the musical and artistic part of the scheme did not pay. In such a state of circumstances there would speedily gather round the place persons and associations of a character calculated to be seriously detrimental to the interests of the school.” (ibid.)

at the time of its opening.

A licence was granted, however, and on 26th November 1875 the Lord Mayor was given a private viewing of the soon-to-be-opened building, followed by dinner at the Westminster Palace Hotel where he was able to discuss the noble enterprise with Lord Londesborough, W.H. Smith, Henry Labouchere, Bruce Phillips and Arthur Sullivan. As opening day approached, press reports kept readers informed about the exciting new venture:

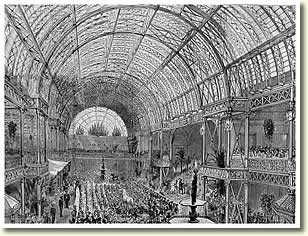

“The original idea of utilising the vacant space on the north side of Tothill Street by erecting a vast building for public instruction and entertainment was due to the fertile brain of Mr. Wybrow Robertson, and an association being formed to carry out the project, Mr. Bruce Phillips being the Secretary, the public took kindly to the idea, and with Mr. A. Bedborough as architect, and Messrs. Lucas as contractors, no time was lost in erecting the Aquarium, the whole period occupied being only eleven months. The architect had no easy task in making such a design as should at once be ornamental in appearance, and yet be available for all the purposes required. The front is divided into compartments by columns, thus avoiding monotony, and the bays are ornamented with groups of sculpture, adding greatly to the artistic effect. The principal entrances are on the Tothill Street side, and the first grand effect upon the mind of the visitor will be made by the great hall, which is 340 feet in length by 160 feet wide. This fine promenade is covered with a roof of glass and iron, and the grace and freshness of a winter garden will be a great attraction, the hall being surrounded by palms and exotic trees and shrubs, the whole having the general aspect of a vast conservatory filled with splendid sculpture. Between these artificial groves fountains will play, and on the opposite side of the entrance is the grand orchestra, capable of accommodating 400 performers, with a large organ. Around the hall are the tanks for the reception of the marine and fresh water creatures. To supply the thirteen tanks lie hid under the floor of the promenade nine great reservoirs – seven for salt and two for fresh water. These are built of brickwork on a four-feet bed of concrete, and will hold 700,000 gallons of water. They are lined with asphalt, and the supply pipes and valves are made entirely of vulcanite, to preserve the salt water from the chemical action which would arise from its contact with iron. The continuous circulation system has been adopted. Towards the north-west corner of the building is a large reading room, wherein tired sight-seers will find English and foreign newspapers, magazines, and other current literature. It is also proposed to collect a complete library of books for reference, to provide convenience for letter writing and materials for the delectation of chess players. There is a telegraph office for the despatch and reception of messages – and furnished, moreover, with a division bell in direct communication with that in the House of Commons, as it is deemed possible that the Royal Aquarium will be largely patronised by both Houses of Parliament. […] The craze of the present day – the [roller-] skating rink is not overlooked, and the lovers of that form of recreation will be able to enjoy themselves at the Aquarium. The Fine Art Exhibition will, it is expected, be one of the features of the Aquarium. A good selection of pictures ought to be made considering that Mr. Millais is at the head of this department. As may be expected, a great number of daubs have been rejected, and Mr. Knight, the Secretary, is somewhat in doubt whether room can be found for all that has been accepted. Music will of course be an important attraction with Mr. Arthur Sullivan as conductor; and a charming little Theatre is also included in the building.” (The Era, 16th January 1876)

Seemingly, the idea was to combine uplifting educational facilities and exhibitions, as provided by the Crystal Palace, with the popular entertainment values of places such as Cremorne Gardens. In a report of the opening ceremony duly held on 22nd January 1876, American readers were treated, with typical transatlantic candour, to a much more colourful, and probably more accurate, assessment of the situation:

“For some time past great expectations have been held out in regard to a grand Royal aquarium which was to be opened in the Westminster district of London, under distinguished patronage. It was to include not only an aquarium, but a concert hall, theatre, a picture gallery, skating rink, Winter garden, drinking bars, restaurant, and a hair-dresser’s shop. A long list of so-called Fellows of this society was published, in which the names of a few persons of rank and distinction figured oddly among a swarm of actors, professional musicians and third-rate men of letters; and it was announced that this wonderful exhibition was “not only to afford amusement, but to widen the scope of knowledge throughout the country, to give visitors to the great metropolis an opportunity of attentively considering some of the most marvellous of the works of creation, and to aid the advancement of science, literature, and art in all its branches”, with more buncombe [sic] of the same sort. The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh, who are supposed to be very anxious to get a platform in public life, were easily secured as patrons of the institution, and the Duchess also undertook to open the building. The latter arrangement was, however, given up for reasons not known, though suspected to be that her Royal and Imperial Highness could not have the Horse Guards for an escort and other accessories of state, and possibly, also, because it was beginning to be seen that there was a screw loose somewhere about the project. The Duke of Edinburgh, however, took the Duchess’ place on Saturday last, when the Royal Aquarium being opened with magniloquent addresses from and to the Duke, was found to be a hollow sham. It was then discovered that the building was still in a very unfinished state, that the tanks for the much-boasted aquarium contained neither water nor fishes, and that the general emptiness of the place was weakly disguised with colored calico and shrubs. It is said, of course, that by and by the exhibition will be got into proper order, but for the present the two-guinea season ticket holders feel themselves swindled, and are making a fierce outcry. The position of the Duke of Edinburgh in this affair is particularly humiliating, and he is said to be much annoyed that he allowed himself to be entrapped into appearing as sponsor for such a piece of humbug. It is reported that the company has not enough money in hand to go on with, and hence the necessity of catching subscribers first, in order to get the means of buying fish afterward.” (New York Times, 12th February 1876)

The address given by the Duke sounded a note of warning:

“In proportion as these laudable purposes are fulfilled you have every right to ask for support and encouragement for this undertaking. I feel assured, gentlemen, that, deeply sensible of the responsibilities which devolve upon you, you will rightly use your trust for the benefit and advantage of the community in a spirit such as alone will render the institution worthy of its splendid situation, and that you will exercise such a watchful care over its future arrangements as in this populace district is urgently demanded.” (The Times, 24th January 1876)

[The Graphic, 29th Jan 1876]

On the inaugural day, Sullivan conducted the orchestra, greatly amplified by the bands of the Scots Fusilier Guards and the Coldstream Guards, in an all-British programme which included his own Procession March, a movement from William Sterndale Bennett’s G minor Symphony and a Festival Overture by George Alexander Macfarren. The prestige of the occasion encouraged the participation of eminent vocal soloists Janet Patey, Edith Wynne and Sims Reeves. Sullivan’s part in the routine arrangements of the Aquarium lay in the selection of repertoire for the twice-daily light orchestral and vocal programmes that were under the conductorship of his ‘assistant’, George Mount (1823-1906). In keeping with the elevated ideals of the institution, more cultured weekly concerts would also take place at 4.00 on Thursday afternoons when Sullivan himself would wield the baton. The first such performance took place on 3rd February when the programme included two movements from Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto and the overtures to Schubert’s Rosamunde and Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Mount, the regular conductor at the Aquarium, was a double-bass player in the Philharmonic orchestra which Wagner conducted in 1855, in 1872 he was a founding member of the short-lived British Orchestral Society and as a result of Sullivan’s frequent absences from the podium during the 1885-1887 Philharmonic Society seasons, he was occasionally called upon to deputise at short notice.

|

|

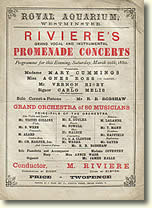

| Programme for 6th March 1876 | Programme for 9th March 1878 |

Sullivan’s commitment to the new venture did not preclude a lengthy sojourn in Paris during March and April, when he tried to interest Jules Pasdeloup in a performance of the Irish Symphony and visited the newly opened Opéra. Returning to London, Sullivan resumed his position as occasional conductor at the Aquarium, but the concerts, hampered by the cavernous acoustic, were not a success. By August he had given up, leaving Mount solely in charge of what reduced musical provision there was. Gradually Mount too lost interest and was succeeded in his duties by Charles Dubois. Other conductors tried to bring musical success to the venue, with varying results:

“On returning to London in the autumn of 1877 I gave, at my own risk, four grand orchestral concerts at the Westminster Aquarium on four consecutive Saturdays. I enlarged the orchestra to eighty musicians, and engaged all the principals from Paris. Besides good singers, I secured the band of the Coldstream Guards, and the experiment, which was a distinct novelty, proved a success, 14,000 visitors passing the turnstiles for the first concert. The net profits for the first four concerts amounted to 300 [pounds], and I much regretted being unable to accept the offer made to me by the directors of the Aquarium to continue the experiment. […] Colonel Mapleson, however, arranged to continue the Saturday concerts I had begun at the Aquarium, and the Italian opera season being over, he was able to have some of the star vocalists from Her Majesty’s Theatre, with Signor Arditi as conductor. Still the concerts were a failure, not certainly owing to lack of quality in the entertainment, but for the same reason that had proved disastrous the year before at the Prince’s Theatre, Manchester. The admission was fixed at 2 [shillings], and 1 [shilling] being the accepted price for promenade concerts, the public showed their resentment of the change by staying away.” (Jules Rivière, My Musical Life and Recollections, 1893, p.193)

Nevertheless, Rivière persevered, giving concerts at the Aquarium into the 1880s and engaging such eminent singers as Mary Davies, Agnes Larkcom, Edward Lloyd and Barton McGuckin. A Javanese orchestra appeared in 1882, whilst in 1885 the Viennese Ladies Orchestra performed: their contribution was possibly more sophisticated than that of the Bozza Troupe two years later, who played

“on an orchestra comprised of plates, frying pans, stew-pans, and other articles de cuisine. [They produced] most astonishing effects from sauce bottles, arranged after the fashion of Pandean pipes.” (The Era, 5th February 1887)

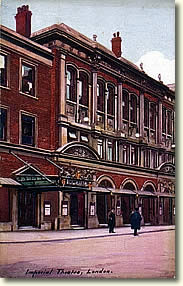

The Royal Aquarium Theatre, designed by Alfred Bedborough to hold an audience of 1,293 playgoers, was originally an important and integral part of the Westminster complex. It belatedly opened on 15th April 1876 with Jo, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House: J.P. Burnett’s dramatisation had proved successful at the Globe Theatre with a strong cast including Jennie Lee and was transferred wholesale. The following year, Gilbert’s 1871 adaptation of Great Expectations was revived but with neither popular nor critical success. Despite a highly enterprising and ever-changing programme, the Aquarium Theatre resolutely failed to attract a sufficient public and closed in 1879. On 1st August that year, newly reopened as The Imperial, it was the venue chosen by the rebellious Comedy-Opera Company for their rival presentation of H.M.S. Pinafore. Subsequently transferred to the Olympic, this production proved less appealing than D’Oyly Carte’s authentic version at the Opera Comique and closed in October after just 91 performances. In 1882 Lillie Langtry would bring success to the Imperial with An Unequal Match by Tom Taylor, but the theatre was never really in the front rank.

The mid-Victorian period truly did witness the dawning of the age of Aquaria, as prominent examples opened at The Crystal Palace (1871), Brighton (1872), Manchester (1874), Southport (1874), Blackpool (1875), Rothesay (1876), Yarmouth (1877), Scarborough (1877) and Tynemouth (1878). Inspired by books such as The Aquarium – An Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea (1854) by Phillip Gosse, and Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), a fascination grew for the peculiar inhabitants of the ocean depths. Some of these new public establishments quickly failed: that in Manchester became a Catholic schoolhouse as early as 1877, whilst the Aquarium at Tynemouth, having cost £82,500, was closed and sold at auction for just £27,000 in 1880. Clearly, it was a risky venture, but some did prosper: Brighton’s Aquarium, ideally situated on the promenade, was close to the Palace Pier and offered brass bands, organ recitals and a roller-skating rink. It certainly needed to be successful, having cost £133,000 to erect.

The Royal Westminster Aquarium, an even more elaborate structure, had required £200,000 to build and was alarmingly costly to maintain, employing 300 regular and a further 700 occasional staff. The Era noted a gradual lapse from the building’s original remit and knew precisely where to point the finger:

“In all cases where a corporate body provides the capital, a dividend is expected, and to pay this it has been found necessary to abandon the lofty ideals propounded in the prospectus issued to the public when the Aquarium was in an embryonic stage.” (The Era, 12th September 1885)

Culture did not pay. In perpetual financial trouble, and with a dwindling public, the Westminster leviathan thus degenerated from a (prospective) temple of learning into a glorified freak-show, albeit a highly enterprising one:

“The fish, though few in number, were on view for some time; in fact, I think that one or two lingered on to the very end twenty-seven years later, in 1903 – but I have always wondered whether anyone went to look at them and if the water was ever changed!

"The Royal Aquarium, in short, was intended to be a sort of Crystal Palace in London within easy reach of Charing Cross, a covered-in promenade for the wet weather, with the glass cases of live fish thrown in. In truth, the attractions of the place soon began to be very ‘fishy’ indeed. Ladies promenaded there up and down without the escort of any gentleman friend (till, maybe, they found one) and the appeal of the management to sensation lovers was very wide indeed. Bare-backed ladies dived from the roof or were shot out of a cannon, or sat in a cage covered with hair and calling themselves ‘Missing Links’. Zulus, Gorillas, Fasting Humans, Boxing Humans and Boxing Kangaroos, succeeded one another in rapid changes, and failed in time to attract.” (Erroll Sherson, London’s Lost Theatres of the Nineteenth Century, 1925, p.297)

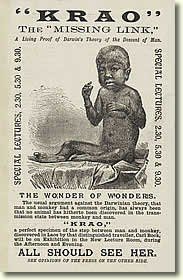

Anthropological curiosities exhibited included “The Two-Headed Nightingale”, apparently vocally-proficient Siamese twins (1885), a three-legged boy from Spain (1898) and (most celebrated of all) Krao “the living missing link, daughter of a tribe of hairy men and women from Laos” (The Times, 3rd January 1883). Press reports sought to justify such a display by emphasising its educational nature:

“Krao possesses in several well-marked particulars the characteristics of a monkey. Still it must be added that in her appearance there is little, if anything, to repel, while beyond doubt there is much to excite a perfectly legitimate interest. There are many who condemn, and perhaps with justice, the taste which takes the form of looking upon ‘freaks of nature’, but Krao, it must be recollected, does not come within this unwholesome category, because her peculiarities are hereditary. Farini has served an attraction which the public are eager to see.” (The Morning Post, 1st January 1883)

Many and varied were the attractions that the Aquarium had to offer, and these were indeed chiefly procured by ‘The Great Farini’ (William Leonard Hunt, 1838-1929). Intent on rivalling the feats of Charles Blondin, Signor Farini crossed Niagara Falls on a tight-rope in 1860 and is also credited with the invention of the device which made possible the very useful practice of firing people out of cannons. In 1877 the Aquarium was the setting for the first female human cannonball act, fourteen-year-old ‘Zazel’ (Rosa Matilda Richter, c. 1863-1937), who launched herself into immortality propelled by huge springs and a counterfeit explosion to the accompaniment of the Zazel Waltz composed by Dubois. She was the inspiration behind a celebrated gag played at the Gaiety Theatre during the run of Little Doctor Faust in 1877:

“Nellie Farren used to get into the cannon and [Edward] Terry would, apparently, ram her down with a big ramrod. Then, after many gags had been cracked and the excitement worked up, the cannon was fired, and Nellie would dash on from the side as if she had been shot far away and just returned. What actually happened was that […] a trap was opened underneath through which she descended, and then ran under the stage and up the other side."One night it all went wrong [and] the trap was never opened. [Terry] did the usual motion and cracked a few gags, and then to his horror he felt that he was ramming the rod, not into an empty cannon, but into a human body. […] It was becoming clear that something was wrong, for the delay began to be apparent, and no amount of gagging could hide it. So Terry gave two or three tremendous digs and then peered into the mouth of the cannon. ‘Are you in?’ he queried. ‘Are you Farren (far in)? Are you Nearly Far In (Nellie Farren).’ [The] puns had made such a hit that they kept them in for the rest of the run.” (W. Macqueen-Pope, Gaiety – Theatre of Enchantment, 1949, p.174)

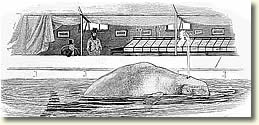

Another talking point, a beluga whale, was introduced to the Aquarium in 1877, but it quickly expired amidst accusations of maltreatment:

“When once the animal was safely deposited in the tank its surroundings were fully as favourable as those of most other creatures when deprived of their natural liberty. The supposed marks of ill-usage on the dead body were the consequences of the eels in the tank having after its death nibbled the edges of its fins.”

(The Times, 3rd October 1877)

In 1880 Agnes Beckwith put the redundant whale tank to good use by treading water in it for 30 hours to equal the record set by Matthew Webb (1848-1883). Webb himself, the most celebrated swimmer of his day, also appeared, giving diving and swimming exhibitions: the first man to successfully swim the English Channel (1875), he was doomed to perish in the swirling surge under Niagara. In November 1887 a Shaving Competition was held and in 1891, Tom Taylor made a staggering break of 1467 during a billiards match, whilst in the new century the first ever table-tennis tournament was hosted by the Aquarium (1901). Alongside the performing fleas (1878), bulls that climbed ladders and rolled on their backs (1883) and packs of wolves (1887), more familiar members of the animal kingdom also found celebrity: cat and dog shows were a popular attraction during the 1880s, those organised by Charles Cruft (1852-1938) being fore-runners of the later events which bore his name.

From time to time, the morals of the clientele who frequented the Aquarium were called into question. Drunks, thieves and prostitutes mingled with the sight-seers and their continued presence led to the London County Council refusing to recommend the renewal of the licence in October 1889. After much debate in the Press, it was eventually conceded that the Aquarium was no better and no worse than many similar establishments: the licence was renewed. Two years later, Professor Emmett presented a living tableau entitled ‘Eve’s Garden’ which

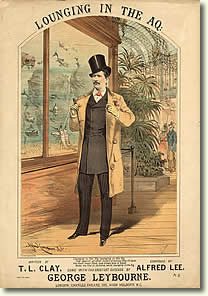

Music Cover

“all married men should see at least once, and those who are single should see as often as they can” (The Music Hall, 25th April 1891).

Music-hall artiste George Leybourne (1842-1884) hymned the delights of the Aquarium’s early days: in his 1879 tribute, after admitting that “I’ve tried all kinds of gaiety”, he declared his true spiritual home

“Lounging in the Aq, lounging in the Aq,

That against all other modes of killing time I’ll back,

Fun that’s never slack, eyes brown blue and black

Make me feel in Paradise while lounging in the Aq”

whilst Arthur Roberts (1852-1933) found success with a song whose suggestive refrain ran

The Royal Aquarium to see;

But I had to stand a bottle just to lubricate the throttle

Of a lady who was forty-three.”

In the 1880s the directors experimented with Musical Hall performances themselves at the Aquarium, but the acts, whilst ideally suited to the intimate and focussed settings of the Halls, withered and failed in the vast echoing spaces of the ‘Tank’, as the Aquarium had come to be known.

The Royal Aquarium was certainly not an abject failure by any means, but neither was it a consistent success, although it did especially well during public holidays:

“The many thousand visitors who thronged this popular resort of amusement from early in the forenoon to close upon midnight yesterday had certainly nothing to complain of in the variety of entertainment provided for them. […] A special feature of the programme is the great Christmas tree laden with children’s toys, the promise being held out that during the holidays every juvenile visitor will be presented with a ticket free on entering the building entitling him or her to select the toy which is fancied the most.” (The Times, 27th December 1887)

“Mr. Josiah Ritchie and his staff at the Royal Aquarium had yesterday to deal with, at the least, three gigantic audiences, and they claimed last night that, in regard at least to attendance, they had achieved a record. Crowds commenced to pour into the great building at Westminster directly the doors were opened at the abnormal hour of 9 o’clock, and the stream of visitors did not cease until a very late hour.” (The Times, 27th December 1894)

Such occasional triumphs were not, however, consolidated by sustained public support. The Royal Aquarium was not the prestigious exhibition space and educational forum initially envisaged, it was not the renowned concert venue originally hoped for, it was not the well-loved variety theatre hinted at in its ever-changing programmes, it was not even an aquarium: it was in fact a circus fairground given unnatural permanence by its pretentious surroundings. Fairs and circuses are by their very nature transient novelties and in this respect it is truly remarkable that the place managed to survive for twenty-seven years.

On 2nd February 1903 the Wesleyan Methodists held a mass meeting at the doomed pleasure-palace to celebrate their purchase of the building, and from the 9th to the 17th February the contents of the Aquarium were auctioned off in 1,691 lots by E. & H. Lumley. Included in the sale were 100 tons of iron grating and hot-water pipes, the grand organ and the stock of wines and spirits. Where the Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden once stood, now indeed stands the Methodist Central Hall – an irony which would no doubt have tickled W.S. Gilbert.

Page modified 30 August 2011