|

|

||||||

by John Sands

During the second half of the nineteenth century operas and ballets were frequently used as the basis for dance arrangements intended both for private and for public performance. The operas of Sullivan were no exception. These attractive pieces are virtually unknown today, whilst comparable dances based on the operettas of Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) are highly regarded and regularly performed. The difference, of course, is that Strauss was responsible for arranging many such pieces himself whilst the names of Sullivan’s arrangers are little more than footnotes in Victorian musical history. Although the dances based on melodies from the Savoy Operas were available from Chappell and Metzler well into the twentieth century, very few copies survive today. There were arrangements for full orchestra, arrangements for small orchestra (septet or octet), and transcriptions for piano duet and piano solo: the Chappell fire in 1964, which destroyed the publisher’s vast archive, took with it orchestral scores, parts and the remainder of the unsold arrangements. The British Library holds orchestral parts for the Lancers, Quadrilles, Waltzes and Polkas based on Princess Ida, The Mikado and Ruddigore (shelfmark e.249), but in the majority of cases there is probably now no extant performing material beyond the piano transcriptions.

It is perhaps fair to say that the first study of these dance pieces tended to be rather dismissive:

“As compositions these arrangements have no great merit. One could arrange a quadrille quite successfully from music from the operas of Balfe or the operettas of Offenbach, since their works were full of rhythmic tunes of regular length. One could likewise arrange attractive independent waltzes from Viennese operettas, as Johann Strauss did in his 1001 Nights and Roses from the South. But one could do relatively little with Sullivan’s music, since his musical settings were more closely allied to the words which inspired them and since he settled for pure dance rhythms much more sparingly.” (Andrew Lamb: Gilbert and Sullivan for dancing. The Gilbert & Sullivan Journal, X, 2, Summer, 1973, p.32)

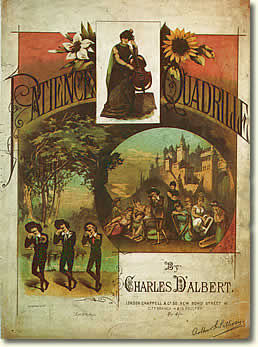

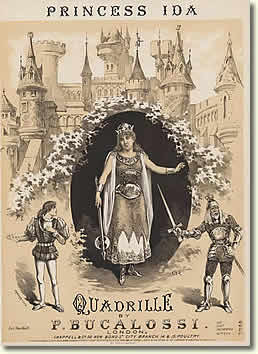

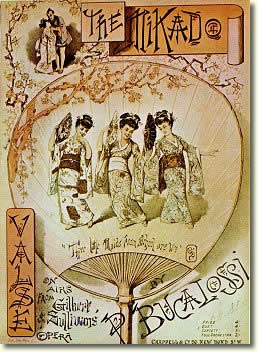

Upon closer examination, however, it can be argued that the skilled musicians who brought Sullivan’s melodies into the ballroom and the parlour did so with a considerable degree of compositional ability, taste and ingenuity. Two musicians dominate the list: Charles Louis Napoléon d'Albert (1809-1886) and Procida Bucalossi (1832-1918). D’Albert emigrated from France with his mother in 1816 and studied for a time, perhaps incongruously in view of his later career, with the eminent church composer Samuel Sebastian Wesley. His early fame came as dancing master at the King’s Theatre and Covent Garden, although he eventually settled in Newcastle-on-Tyne and returned to London only during the latter part of his life. Enormously prolific, his most popular original pieces included the Sultan’s Polka and the Edinburgh Quadrille. D’Albert produced dances based on Trial by Jury, The Sorcerer, The Pirates of Penzance, Patience and Iolanthe. From 1884 the mantle passed to Procida Bucalossi who had responsibility for arrangements based on Princess Ida, The Mikado, Ruddigore, The Yeomen of the Guard, The Gondoliers, Haddon Hall and The Grand Duke. These were highly prestigious commissions: such was the fame of the Savoy Operas that these arrangements were available in all corners of the Empire.

Bucalossi, like d'Albert, was a prolific dance composer in his own right. His highly successful waltzes included My Queen (1881), Mia Cara (1883) and Beauty and the Beast (1890), based on music for a Drury Lane pantomime. He contributed one act to the collaborative ballet Rothomago (Alhambra, 1879), part of which was composed by Edward Solomon. Bucalossi also enjoyed success with three operas, Monsieur Pom (1876), Les Manteaux Noirs (1882) and Delia (1889), the second of which ran for over a year at the Avenue Theatre, London. In 1895 he was interviewed for The Strand Musical Magazine and explained his working methods:

“In arranging dance music from operas, the plan I have always adopted is to select the liveliest melodies for Lancers and Quadrilles, and the sentimental for valses. The great thing is not to change the Tempo of the original composition if possible, but in many cases this has to be done. The original harmonies should also be preserved, when possible, with the arrangements, and this, again, is often very difficult.”

Other prominent musicians were involved in crafting dances based on Sullivan’s melodies. Responsibility for the sets of Lancers based on H.M.S. Pinafore and Princess Ida fell to Charles Coote, Junior (1831-1916), whilst the majority of the dances based on H.M.S. Pinafore were created by Charles Godfrey (1839-1919). Godfrey, a member of a vast musical dynasty, taught military music at the Royal College and the Guildhall School in addition to his duties as bandmaster successively to the Scots Fusiliers (1859-1868) and the Royal Horse Guards (1868-1904). For the military band market, he also supplied quick marches based on The Sorcerer, H.M.S. Pinafore and Princess Ida.

Also interviewed for The Strand in 1895, Coote, whose most popular original compositions included the Prince Imperial Galop (1865), the Queen of the Harvest (1857) and Cornflower (1877) waltzes and the polkas Great Eastern (1859) and Bric-a-Brac (1878), offered the opinion that

“the most important feature of a popular dance, apart from the melody, should be its simplicity. Many compositions of this class would gain far greater popularity if the composer were but to remember that the majority of those who play the piano for their own amusement are not accomplished musicians, though possibly able to play ordinary music with taste.”

Indeed, it should be borne in mind that the pieces under present discussion (unlike many of those by Strauss) were not intended to be concert-works but fulfilled instead an entirely functional dual purpose. On the one hand they helped to supply the constant stream of novelties demanded by the ballroom and the domestic pianist, and on the other they brought valuable extra revenue to Sullivan and to his publishers.

In the catalogue of derivative arrangements based on the Savoy Operas one curiosity is the Waltz based on The Chieftain. In the published vocal score, Boosey advertised the piece as being by Zavertal whereas the actual sheet music describes the arrangement as “by Arthur Sullivan”. Czech-born Ladislao Josef Filip Pavel Zavertal (1849-1942) was a prominent figure in late-Victorian band music. In 1881 he was appointed to a post at the Royal Artillery in Woolwich and there he set about raising musical standards and developing an orchestra with which he gave well-received concerts at St James’s Hall, Queen’s Hall and the Royal Albert Hall between 1889 and 1905. Zavertal’s involvement with The Chieftain encompassed both the Waltz and the construction of a more elaborate Selection from the opera. Perhaps due to the constant alterations that Burnand and Sullivan were making to the The Chieftain early in 1895 in order to bolster its run, three months after the opera had opened the Waltz was still unpublished. In March 1895, Sullivan wrote to Zavertal from No. 1 Queen’s Mansions:

“I am extremely vexed that you should have waited so long for me yesterday, and that I missed the pleasure of seeing you. I rarely go out so early in the day, and I need scarcely say that it was business of importance that kept me so long. I think the quickest thing now is for me to write out the Valse for the Pianoforte, & send it to you to score for Orchestra. You have experience of Dance Music and will do it much better than I can.” (Glasgow University Library, MS Zavertal Cb 13-y.5/15)

Over the following days Sullivan clearly worried at the task of shaping the waltz and wrote again to Zavertal:

“I send you with this the sketch of the Valse I have done from the “Chieftain” – I have not written out a complete Pianoforte arrangement, as I thought the sketch (as it is) would be as much as you require. I have only written out the melody, & indicated the harmony. […] you have the experience of scoring for a large orchestra, in such a manner that it will be effective for a smaller one when required. This is where experience comes in. I can do it, but I am slow at it, and it is really not very easy to do in a musicianly way.” (ibid)

This is the only known instance where a dance arrangement of Sullivan’s music was actually undertaken by the composer himself. If the 1870s and 1880s saw Bucalossi succeed d'Albert as the dance arranger par excellence, the latter part of the 1890s and the early years of the twentieth century were dominated by two new names, Warwick Williams (1846-1915) and Carl Kiefert (1855-1937). This period saw the heyday of Musical Comedy and the constant production of new shows, all of which required dance arrangements, kept both men very busy. According to his obituary in The Musical Times Williams had once served as Sullivan’s Secretary, whilst Kiefert was Musical Director of many London productions including Gilbert and Carr’s His Excellency (1894), Sidney Jones’ An Artist’s Model (1895), Leslie Stuart’s Florodora (1899) and Lionel Monckton’s A Quaker Girl (1910). His acknowledged expertise and speed at instrumentation made Kiefert the most sought-after arranger of theatre scores and he regularly orchestrated for Lionel Monckton and Osmond Carr. Other musicians involved in creating dance music from Sullivan’s operas included William Henry Montgomery (1810-1886) and the organist Frederic Ralph Kinkee (1858-1915).

In their efforts to translate Sullivan’s melodies into dance rhythms, the primary task of the arrangers was to bring to the themes a metrical predictability that Sullivan had originally striven hard to avoid. In his Lancers based on The Gondoliers, Bucalossi adjusted the melody of And if ever, ever, ever they get back to Spain to provide a simple and neatly-closed tune

(ex. 1) ![]() , as did d'Albert in treating the introduction to Ruth’s Song in The Pirates of Penzance Lancers (ex. 2)

, as did d'Albert in treating the introduction to Ruth’s Song in The Pirates of Penzance Lancers (ex. 2) ![]() : these were straightforward and easily-accomplished alterations achieved with minimum fuss. Likewise, in an extract taken from the Ruddigore Quadrille, Bucalossi simply halved the note values of the final phrase in order to bring it within the confines of the required sixteen-bar structure (ex. 3)

: these were straightforward and easily-accomplished alterations achieved with minimum fuss. Likewise, in an extract taken from the Ruddigore Quadrille, Bucalossi simply halved the note values of the final phrase in order to bring it within the confines of the required sixteen-bar structure (ex. 3) ![]() . Occasionally more drastic measures were taken: in his Quadrille based on Utopia Limited Frank Leslie boldly omitted whole sections of a melody in order to make it fit (ex. 4)

. Occasionally more drastic measures were taken: in his Quadrille based on Utopia Limited Frank Leslie boldly omitted whole sections of a melody in order to make it fit (ex. 4) ![]() as Godfrey had done fifteen years before in his H.M.S. Pinafore Quadrille (ex. 5)

as Godfrey had done fifteen years before in his H.M.S. Pinafore Quadrille (ex. 5) ![]() . Both are successful adaptations in that the re-constructions are logical and satisfying in their own right. Greater subtlety was displayed by d'Albert in shifting the rhythmical emphasis of a theme in the Trial by Jury Lancers (ex. 6)

. Both are successful adaptations in that the re-constructions are logical and satisfying in their own right. Greater subtlety was displayed by d'Albert in shifting the rhythmical emphasis of a theme in the Trial by Jury Lancers (ex. 6) ![]() whilst Bucalossi went to town in The Mikado Waltz (ex. 7)

whilst Bucalossi went to town in The Mikado Waltz (ex. 7) ![]() , completely transforming the rhythm and extending the melody of what was originally Are you in sentimental mood. Similarly accomplished is Paul Duprêt’s elegant treatment of In such a case, Upon your breast in his Utopia Limited Waltz (ex. 8)

, completely transforming the rhythm and extending the melody of what was originally Are you in sentimental mood. Similarly accomplished is Paul Duprêt’s elegant treatment of In such a case, Upon your breast in his Utopia Limited Waltz (ex. 8) ![]() . Sometimes an original melody could have undergone more than one of these processes in its transformation and d'Albert and Bucalossi were outstanding masters of this delicate art, shown at its best in the arrangements from Iolanthe (Quadrille, ex. 9)

. Sometimes an original melody could have undergone more than one of these processes in its transformation and d'Albert and Bucalossi were outstanding masters of this delicate art, shown at its best in the arrangements from Iolanthe (Quadrille, ex. 9) ![]() and The Mikado (Quadrille, ex. 10)

and The Mikado (Quadrille, ex. 10) ![]() . Not content with being wholly reliant upon Sullivan’s store of tunes, d'Albert could not resist interpolating ideas of his own into such pieces as the Trial by Jury Quadrille (ex. 11)

. Not content with being wholly reliant upon Sullivan’s store of tunes, d'Albert could not resist interpolating ideas of his own into such pieces as the Trial by Jury Quadrille (ex. 11) ![]() and the Patience Waltz (ex. 12)

and the Patience Waltz (ex. 12) ![]() : no other arranger displayed such audacity.

: no other arranger displayed such audacity.

In one particular case we have the opportunity to directly compare the different methods and skills of two arrangers. The Lancers and Quadrille on Princess Ida were constructed by Coote and Bucalossi respectively, and they perhaps explain the pre-eminence of Bucalossi following the retirement and death of d'Albert. Both Coote and Bucalossi made a similar selection of melodies from the opera but whilst Coote’s treatment of the more metrically-and harmonically-regular themes is excellent, in two instances the greater dexterity of Bucalossi is apparent. In his adaptation of Would you know the kind of maid Coote follows Sullivan’s original harmonic scheme faithfully but the necessity to shorten the melody results in a rather undignified scramble before the first double bar (ex. 13) ![]() . Faced with the same problem, Bucalossi nonchalantly cuts the theme short and forgoes the harmonic subtleties of the original with far more convincing results (ex. 14)

. Faced with the same problem, Bucalossi nonchalantly cuts the theme short and forgoes the harmonic subtleties of the original with far more convincing results (ex. 14) ![]() . In utilising For a month to dwell in a dungeon cell, Coote again is more faithful to the original to the detriment of the dance: we lose our sense of the structure (four phrases, each of four bars) and the close comes as a rather disconcerting surprise (ex. 15)

. In utilising For a month to dwell in a dungeon cell, Coote again is more faithful to the original to the detriment of the dance: we lose our sense of the structure (four phrases, each of four bars) and the close comes as a rather disconcerting surprise (ex. 15) ![]() . In contrast, Bucalossi is confident and expert in his cutting of Sullivan’s original material thus retaining a much more balanced structure for the listener (ex. 16)

. In contrast, Bucalossi is confident and expert in his cutting of Sullivan’s original material thus retaining a much more balanced structure for the listener (ex. 16) ![]() .

.

Whilst the Mikado Waltz shows a successful flight of fancy by Bucalossi, less endearing is Warwick Williams’ treatment of the stately triple-time chorus As before you we defile. In order to accommodate the original melody into the required duple-time, it is contorted into an awkward and unsatisfying parody of itself (ex. 17) ![]() . However, this is a very rare instance of failure and the rest of his Lancers based on The Grand Duke is delightful. No less than three arrangers were involved in the Utopia Limited dances and there is a sense that they were chasing after the same scarce melodic resources since there is an unusually large amount of duplication between the Lancers by Kinkee and the Quadrille by Frank Leslie. The best arrangements by d'Albert have a stylish elegance and show a sophisticated awareness of thematic transformation: it would take a keen ear to detect that the origin of a beguiling theme in The Sorcerer Waltz lies in Alexis’ Thou hast the pow’r thy vaunted love

. However, this is a very rare instance of failure and the rest of his Lancers based on The Grand Duke is delightful. No less than three arrangers were involved in the Utopia Limited dances and there is a sense that they were chasing after the same scarce melodic resources since there is an unusually large amount of duplication between the Lancers by Kinkee and the Quadrille by Frank Leslie. The best arrangements by d'Albert have a stylish elegance and show a sophisticated awareness of thematic transformation: it would take a keen ear to detect that the origin of a beguiling theme in The Sorcerer Waltz lies in Alexis’ Thou hast the pow’r thy vaunted love

(ex. 18) ![]() . Bucalossi’s dances may not be quite so refined, but they have an infectious gaiety and display both technical assurance and a supreme mastery of the idiom: faced with the metrical irregularities of Were I thy bride, it is difficult to imagine anybody achieving a more satisfying solution than the one contained in his Yeomen of the Guard Quadrille (ex. 19)

. Bucalossi’s dances may not be quite so refined, but they have an infectious gaiety and display both technical assurance and a supreme mastery of the idiom: faced with the metrical irregularities of Were I thy bride, it is difficult to imagine anybody achieving a more satisfying solution than the one contained in his Yeomen of the Guard Quadrille (ex. 19) ![]() . A similar adaptation replete with elisions and contractions expertly transforms How would I play this part in The Grand Duke Quadrille by Warwick Williams (ex. 20)

. A similar adaptation replete with elisions and contractions expertly transforms How would I play this part in The Grand Duke Quadrille by Warwick Williams (ex. 20) ![]() . For more than a century these dances have been prized for their beautiful illustrated covers, perhaps they should also now be cherished for the musical artistry they represent.

. For more than a century these dances have been prized for their beautiful illustrated covers, perhaps they should also now be cherished for the musical artistry they represent.

The earliest arrangement to be published was a Quadrille by Charles Coote based on Cox and Box (Boosey, 1873). Subsequent pieces drawn from Sullivan’s operas are summarised below. The plate numbers of the piano solo arrangements are included to indicate chronology and aid identification, whilst an asterisk signifies the issue of a companion publication for piano duet. In the case of the Polkas based on H.M.S. Pinafore, Princess Ida, The Mikado, Ruddigore and The Gondoliers a duet was listed on the sheet music cover, but contemporary advertisements referred only to the availability of a solo arrangement. There were no derivative dances from either Ivanhoe or The Beauty Stone.

| Title | Plate No. | Arranger | Publisher | Date |

| Trial by Jury Galop* | 16065 | W. H. Montgomery | Chappell | 1876 |

| Trial by Jury Lancers* | 16072 | Charles d'Albert | Chappell | 1876 |

| Trial by Jury Waltz* | 16129 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1876 |

| Trial by Jury Polka* | 16130 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1876 |

| Trial by Jury Quadrille* | 16293 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1876 |

| The Sorcerer Lancers* | M4868 | d'Albert | Metzler/ Chappell | 1878 |

| The Sorcerer Quadrille* | M4869 | d'Albert | Metzler/ Chappell | 1878 |

| H.M.S. Pinafore Quadrille* | M4931 | Charles Godfrey | Metzler | 1878 |

| H.M.S. Pinafore Galop* | M4944 | Godfrey | Metzler | 1878 |

| The Sorcerer Waltz* | M5011 | d'Albert | Metzler/ Chappell | 1878 |

| H.M.S. Pinafore Waltz* | M5081 | Godfrey | Metzler | 1878 |

| H.M.S. Pinafore Lancers* | M5109 | Charles Coote | Metzler | 1878 |

| H.M.S. Pinafore Polka* | M5198 | Godfrey | Metzler | 1878 |

| The Pirates of Penzance Lancers* | 17065 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1880 |

| The Pirates of Penzance Quadrille* | 17074 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1880 |

| The Pirates of Penzance Waltz* | 17090 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1880 |

| The Pirates of Penzance Polka | 17094 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1880 |

| The Pirates of Penzance Galop* | 17096 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1880 |

| Patience Quadrille* | 17181 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1881 |

| Patience Lancers* | 17183 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1881 |

| Patience Polka* | 17188 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1881 |

| Patience Waltz* | 17192 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1881 |

| Iolanthe Lancers* | 17647 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1883 |

| Iolanthe Quadrille* | 17650 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1883 |

| Iolanthe Polka* | 17651 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1883 |

| Iolanthe Waltz* | 17657 | d'Albert | Chappell | 1883 |

| Princess Ida Waltz* | 17887 | Procida Bucalossi | Chappell | 1884 |

| Princess Ida Quadrille* | 17888 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1884 |

| Princess Ida Lancers* | 17891 | Coote | Chappell | 1884 |

| Princess Ida Polka* | 17893 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1884 |

| The Mikado Polka* | 18041 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1885 |

| The Mikado Waltz* | 18046 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1885 |

| The Mikado Lancers* | 18048 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1885 |

| The Mikado Quadrille* | 18051 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1885 |

| Ruddigore Lancers* | 18329 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1887 |

| Ruddigore Waltz* | 18330 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1887 |

| Ruddigore Quadrille* | 18333 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1887 |

| Ruddigore Polka* | 18334 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1887 |

| The Yeomen of the Guard Lancers* | 18605 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1888 |

| The Yeomen of the Guard Quadrille* | 18610 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1888 |

| The Yeomen of the Guard Waltz* | 18611 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1888 |

| The Gondoliers Waltz* | 18861 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1890 |

| The Gondoliers Lancers* | 18862 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1890 |

| The Gondoliers Quadrille* | 18864 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1890 |

| The Gondoliers Polka* | 18865 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1890 |

| Haddon Hall Quadrille | 19367 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1892 |

| Haddon Hall Lancers* | 19368 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1892 |

| Haddon Hall Polka | 19371 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1892 |

| Haddon Hall Waltz* | 19374 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1892 |

| Utopia Limited Quadrille | 19558 | Frank Leslie | Chappell | 1893 |

| Utopia Limited Waltz* | 19561 | Paul Duprêt | Chappell | 1893 |

| Utopia Limited Lancers* | 19565 | F. R. Kinkee | Chappell | 1893 |

| Utopia Limited Polka | 19567 | Duprêt | Chappell | 1893 |

| The Chieftain Polka | H1303 | Kinkee | Boosey | 1895 |

| The Chieftain Lancers | H1304 | Kinkee | Boosey | 1895 |

| The Chieftain Waltz | H1354 | Arthur Sullivan | Boosey | 1895 |

| The Savoy Lancers | 19853 | William Moore | Chappell | 1895 |

| The Grand Duke Lancers | 20095 | Warwick Williams | Chappell | 1896 |

| The Grand Duke Quadrille | 20097 | Williams | Chappell | 1896 |

| The Grand Duke Waltz | 20103 | Bucalossi | Chappell | 1896 |

| The Rose of Persia Lancers | 20918 | Williams | Chappell | 1900 |

| The Rose of Persia Waltz | 20937 | Carl Kiefert | Chappell | 1900 |

| The Emerald Isle Lancers | 21311 | Williams | Chappell | 1901 |

| The Emerald Isle Waltz | 21324 | Kiefert | Chappell | 1901 |

Scores of piano versions of many of these arrangements

Page modified 4 April 2010